-

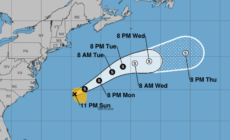

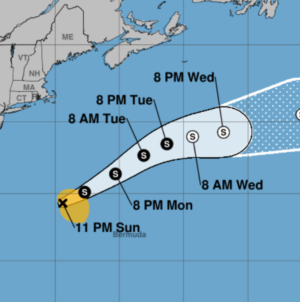

Tropical Storm Dexter Tracker Shows Path Across Atlantic - 16 mins ago

-

Noah Lyles Shoved by Kenny Bednarek After USATF Men’s 200-Meter Final - 22 mins ago

-

Dolly Parton modified iconic Playboy bunny costume for ‘Bible-totin’ fans: author - 32 mins ago

-

Football Star Dominik Szoboszlai Welcomes First Child - 49 mins ago

-

Number of Americans Selling Their Home Hits Major Milestone - 55 mins ago

-

New Medicaid federal work requirements mean less leeway for states - about 1 hour ago

-

TBT 2025 Championship Recap: Aftershocks Top Eberlein Drive To Claim Title - about 1 hour ago

-

No Social Security Payment Is Being Paid This Week. Here’s Why - 2 hours ago

-

Rangers’ Jacob deGrom Is Fastest to 1,800 Career Strikeouts in MLB History - 2 hours ago

-

Meghan Markle turns 44 as she works on new Netflix deal agreement: experts - 2 hours ago

Real Reason Behind Birth Rate Decline

Countries all over the world are facing declining birth rates, sparking fears there will one day be more elderly people than working-age people to support them.

For example, in the United States, the fertility rate (the average number of children a woman has in her lifetime) is now projected to average 1.6 births per woman over the next three decades, according to the Congressional Budget Office’s latest forecast released this year. That is below the replacement rate of 2.1 births per woman required to maintain a stable population without immigration.

Financial struggles are often cited as the reason for people having fewer or no children, but recent research has focused on cultural changes.

Newsweek has pulled together the main reasons birth rates are declining to build a detailed picture of the issue many governments are trying to tackle.

Newsweek Illustration/Canva/Getty

Financial Worries

The 2008 financial crisis and its impact on housing, inflation and pay is generally cited a major contributor to people’s decisions to delay having children, to have fewer children or not to have them at all.

In June, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) found that 39 percent of the 14,000 people across the 14 countries it surveyed said financial limitations prevented them from having their desired family size.

“Young people overwhelmingly report worries and uncertainty about their futures. Many expect to experience worse outcomes than their parents did,” the report said. “Their concerns about climate change, economic instability and rising global conflicts will be reflected in the choices they make about raising families.”

U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration has taken steps to try to tackle the concerns, including the White House exploring giving women a “baby bonus” of $5,000, according to an April report in The New York Times.

The country could also make childbirth free for privately insured families, with the bipartisan Supporting Healthy Moms and Babies Act, which would designate maternity care as an essential health benefit under the Affordable Care Act, which was introduced in the Senate in May.

Family Policies

Policies around child care and parental leave come up just as often as financial struggles—and the two are often connected.

“Countries that have sustained or moderately increased birth rates—like France or the Nordic nations—have done so by investing in affordable child care, paid parental leave, gender-equal workplaces and housing support,” said Poonam Muttreja, executive director of the Population Foundation of India.

“These create an enabling environment where people feel secure in having children,” she told Newsweek. “Fertility decisions are shaped by long-term confidence, not one-off cash handouts.”

Similarly, Theodore Cosco, a research fellow at The Oxford Institute of Population Ageing, told Newsweek that “addressing declining birth rates would require comprehensive support mechanisms, such as affordable child care, paid parental leave, health care access and economic stability.”

Gender Inequality

Another linked aspect to this is gender inequality—a cause often stressed by Muttreja. While speaking about the situation in India, where the fertility rate is 1.9, according to World Bank data, she called gender inequality a “critical challenge.”

“No country has become economically advanced without a substantial participation from women in the economy,” she previously told Newsweek. “The burden of caregiving, whether for children or elderly family members, falls disproportionately on women, and policies must enable women to balance work and caregiving effectively.”

Tomas Sobotka, deputy director of the Vienna Institute of Demography, told Newsweek: “Recent research emphasizes that fertility tends to be higher where gender equality is stronger, and where institutional support helps reduce the cost and complexity of raising children.”

He cited France and Sweden as examples. While their fertility rates have still plummeted in the past decade (1.66 and 1.45, respectively, according to World Bank data), they are higher than the European Union (1.38).

This is “partly thanks to generous family policies with affordable child care, well-paid parental leaves and generous financial benefits to families,” he said. “These, together with high levels of gender equality, make it easier especially for the better educated women and couples to achieve the number of children they planned.”

Cultural Shifts

Another major, albeit more difficult to measure, contributor is a shift in cultural values.

A new study conducted by academics affiliated with the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) published last month found that “short-term changes in income or prices cannot explain the widespread decline” in fertility but rather there has been a “broad reordering of adult priorities with parenthood occupying a diminished role.”

Authors Melissa Schettini Kearney, an economist from the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, and Phillip B. Levine, an economist from Wellesley College in Massachusetts, found there have been “changes in how much value people place on different life choices, generally reflecting a greater emphasis on personal fulfillment and career.”

These include the fact that most women in high-income countries now work, while it was previously “reasonable to consider having children as a widespread priority for women.”

But they do not attribute this to “whether women work at all after they are married or have had their first child” but rather “the tension between a lifetime career and the way motherhood interrupts or alters that lifetime career progression.”

Kearney and Levine also spoke about changes in preferences in general, citing several surveys they reviewed that showed that more people say having a career they enjoy and close friends is extremely or very important than those who say the same about having children.

They also mentioned changes in parenting expectations, with it becoming “more resource- and time-intensive” than before, a reduction in marriages, access to effective contraception, abortion policies, fertility and infertility treatments.

These reasons became clear when Newsweek looked at Norway, which is considered a global leader in parental leave and child care policies, with the United Nations International Children’s Fund (UNICEF) ranking it among the top countries for family-friendly policies.

Norway offers parents 12 months of shared paid leave for birth and an additional year each afterward. It also made kindergarten (similar to a U.S. day care) a statutory right for all children age 1 or older in 2008.

Yet, Norway’s fertility rate has dropped drastically from 1.98 in 2009 to 1.44 in 2024, according to official figures. The rate for 2023 (1.40) was the lowest recorded fertility rate in the country.

Newsweek spoke with several local experts about Norway and all cited recent cultural changes, including lower rates of couple formation for those in their 20s, young adults being more likely to live alone and the demands of modern parenting.

What Is The Solution?

“The short answer is that there are no easy fixes,” Kearney and Levine said in their report. “There is no single policy lever that will reliably boost fertility.”

Kearney and Levine’s main call to action is to “widen our lens” when discussing fertility.

“There is still so much more we need to know before we can provide something resembling a definitive answer,” they said.

“Policies like parental leave, child care subsidies, baby bonuses, etc., are much easier to implement and have the potential to affect fertility more rapidly, if they were effective,” Levine told Newsweek. “Changing the social conditions that encourage family formation is more difficult and takes longer to accomplish.

Source link