-

Saudi Arabia vs. Norway: How to Watch, Odds, U-20 Preview - 8 mins ago

-

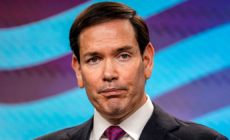

Marco Rubio says ongoing Gaza peace talks are ‘not yet’ the end of the war - 18 mins ago

-

Cowboys Vet Sends His Brother a Message Before Battle vs Jets - 21 mins ago

-

Nigeria vs. Colombia: How to Watch, Odds, U-20 Preview - 52 mins ago

-

How to Watch Newcastle United vs Nottingham Forest: Live Stream Premier League, TV Channel - about 1 hour ago

-

English far-right leader Tommy Robinson invited to Israel - about 1 hour ago

-

NFL International Series: How to Bet on the Vikings vs Browns NFL London Game - 2 hours ago

-

Eric Dane vows to ‘fight to the last breath’ against ALS in visit to Washington - 2 hours ago

-

Donald Trump Pleads for ‘Google/YouTube’ Change Before Midterms - 2 hours ago

-

Pope Leo, after Trump critique, urges Catholics to help immigrants - 2 hours ago

Public school is a right. Should child care be considered one too?

Since the pandemic, the cry for more affordable, accessible child care has grown ever louder. The annual cost to put a child in day care can be more than college tuition or even a mortgage payment for American families. Many advocates have called on the United States to fund a robust federal child-care system similar those in most other developed countries.

The problem is that advocates have been framing the issue all wrong, researcher Elliot Haspel argues in his new book, “Raising A Nation.” Haspel, a senior fellow at Capita, a family policy think tank, says the popular economic argument — that child care is needed for parents to go to work, feed their families and contribute to the economy — doesn’t carry the moral heft to convince enough voters of its importance.

Instead, Haspel said, child care needs to be reframed as an American value with many advantages — including family creation and even national security. The Los Angeles Times spoke with Haspel about “Raising A Nation,” and the key arguments he believes should appeal to all Americans. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Engage with our community-funded journalism as we delve into child care, transitional kindergarten, health and other issues affecting children from birth through age 5.

How do you hope the book will be used to help advocates build a more effective child-care movement?

The pandemic shone a very bright light on just how important child care was, and we’ve seen more attention to it from both blue states and red states, and both Republicans and Democrats. But it doesn’t feel like we’re necessarily on track for a massive, transformative policy change.

My contention is that part of the reason is because of the way we frame the issue. If we continue as advocates to talk about it mostly as private good that helps parents work, we’re not going to get where we need to go. The playbook is not working. I think we have to switch things up.

Why do you say the popular economic argument is valid but “morally impoverished”?

Lots of things help people go to work and provide financially for their families. I use the example of a car. In most places in this country, having access to a car is a necessary step to getting to work … but we don’t think of [having a] car a moral right. We think of it as a private service or commodity, which you have to figure out. And if you have trouble figuring it out, you can’t really ask the government for help.

When we talk about something in economic terms, it really doesn’t have much moral valence. But when you think about the right to public school — which, by the way, also help people go to work and put a roof over their head and help businesses be more productive — the rationale behind spending $800 billion a year of public money is much deeper than that. It’s much more about what does it mean for families, for communities and for the country as a whole.

How do you get people excited about public funding for child care when they don’t have children or no longer need child care?

I don’t think it’s hard for most people to make the mental leap that, ‘I need there to be strong schools in my community.’ The vast majority of time that a school bond measure comes up in communities around the country, voters approve it — and that requires voters who do not have children. But because we haven’t asserted the broader value of child care and all the ripple effects, it’s harder for people to see themselves in it.

Everyone has a self-interest in [child care], even if they don’t understand it yet. How many people understand that ambulance services can fail if an emergency worker can’t go to work because of a child-care breakdown? Someone could be 80 years old and not have any kids, and it still really matters when they call 9-1-1, that the ambulance shows up to their house in a timely manner. We need to make that case.

I think the towns and places that get it the most are some of these rural towns. Individual residents might not plan to use a child-care center, but if we don’t have a center, there’s not going to not going to be anyone with kids in this town anymore because families will move away. They are literally not going to exist in 20 years.

What do you think is the most compelling argument in favor of universal child care?

I think it is the family case.

Family is a value that is held so strongly by Americans of all stripes, all political persuasions, and the idea that we have families in this country that cannot spend quality time together, that cannot live in the communities they want to live in, that cannot go to religious institutions together, have the number of kids that they want, or parent the way they want to parent — all because as a country we’ve decided child care is this individual responsibility that government isn’t going to get involved with.

To me, this weakens every part of our society. It weakens our families. It weakens our communities. It weakens the country. And I think the more we can say, ‘Here is the vision of what we could accomplish with good child care,’ I think that has real potential to move people.

How should we think about paid family leave?

I am absolutely convinced that we need to tether paid family leave and child care together tightly. Paid parental leave is infant child care, full stop.

Good paid leave relieves the pressure on the external child-care system. Infant care is the most expensive to provide and the most difficult to provide. It requires the most regulatory compliance for their health and safety, and the lowest child to adult ratios. So the more we can remove the need for external care for infants — which also is when most parents would prefer to be home with their children — that is also good. There really shouldn’t be a conversation about child care policy that doesn’t include paid leave.

I think the more we can say infants will largely be covered by paid leave, it’s also a less charged conversation. My experience is people have much, much less of a negative reaction to the idea of a toddler in a licensed child-care program than they do the idea of a baby.

What arguments were effective in other countries that have robust child-care systems?

The U.S. child-care system is one of the lowest-funded systems, and one of the worst systems in terms of affordability and access. I’m talking about the U.S. compared to Germany, France, Canada, Australia.

What’s interesting though, is that a lot of these countries have made big reforms just in the past 20 years. Are these systems perfect? No, but it does show that larger form is possible. And different arguments have worked in different places. Usually it has been a combination of gender equity arguments, some economic arguments for sure, and then tying into this idea of this should be a right. I think it’s notable how many of these efforts were led by women leaders.

The federal government is in cutback mode, including Head Start. Where do advocates go from here?

I think it’s proper to be in a defensive stance.

When I look at states, I find some hope. And it’s not just the blue states. Texas is putting in $100 million into their child-care system; Montana carved out a trust fund for early care and education; and Kentucky is making child care free. Many red states are starting to accept that there needs to be some kind of government role.

Now, do I think anything at the federal level is going to happen between now and 2029? Absolutely not. That is highly unlikely. But I think there’s something to be said for using this time in the federal wilderness, at the national level, to be rethinking this strategy.

This article is part of The Times’ early childhood education initiative, focusing on the learning and development of California children from birth to age 5. For more information about the initiative and its philanthropic funders, go to latimes.com/earlyed.

Source link