-

For California delegation and its staffers, here’s what shutdown life looks like - 11 mins ago

-

Gen Zer Tries On ‘Historically Accurate’ Y2K Item—Can’t Cope With Result – Newsweek - 12 mins ago

-

Arrests over jewel heist at the Louvre, French prosecutors say - 18 mins ago

-

What game is Tom Brady calling today? Week 8 schedule - 27 mins ago

-

L.A. County’s $4-billion question: How to vet sex abuse claims? - 50 mins ago

-

Putin Hails ‘Unique’ Nuclear-Powered Cruise Missile After Latest Test - 51 mins ago

-

NFL Week 8 Injury Report, Inactives: QBs Lamar Jackson, Jayden Daniels Out - about 1 hour ago

-

Louvre Heist Update: Two Arrested After Daring Theft of Historic Jewelry - 2 hours ago

-

'We were able to PUNCH back' 😤 Will Smith on Yamamoto, Dodgers' Game 2 WIN vs Blue Jays - 2 hours ago

-

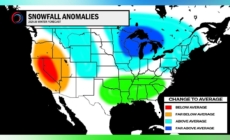

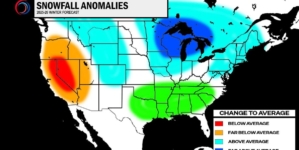

La Niña map shows snowfall forecast for each state this winter - 2 hours ago

Sunday school led on to silver screen and much more

The very first thing on the silver screen as the film begins is a roaring lion – that’s MGM. Or a pulsing radio tower sitting atop a spinning globe – that’s RKO. Or the goddess-like Torch Lady in a robe on a pedestal – Columbia Pictures. The pyramidal mountain in a ring of stars is Paramount, the Germanic castle is Disney, Universal Pictures has a rotating Earth and stars, Warner Brothers the WB shield, Fox’s searchlights. And then there’s the muscular Gongman…

Dong! Dong! Twice the Gongman strikes, and the words “J. ARTHUR RANK PRESENTS” appear over the gong, so sit back for an hour-plus of solid British entertainment – a scatterbrain Norman Wisdom comedy perhaps, or one of the lightly amusing “Doctor” series, or a Powell and Pressburger drama such as the nun-gone-mad “Black Narcissus”, an early Hitchcock thriller, some “Carry On” titillation, a David Lean Dickens, the veteran car jape “Genevieve”, the fatal crunch with an iceberg in “A Night To Remember”?

Gareth Owen offers us the story of Joseph Arthur Rank, born in Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, England, on December 22, 1888 who became a millionaire flour miller and was a devout teetotalling Methodist, then got into films only to spread the gospel. Rank presented religious films at his local Sunday school but after running out of fresh ones he decided to make his own, eventually going on to create the greatest film empire Britain had ever seen.

Initially, Rank had no interest or desire to be involved in commercial films, although he was acutely aware of their influence on modern-day life and society. He met John Corfield, who had produced a low-budget film, and Corfield introduced him to Lady Annie Henrietta Yule, a millionairess widow of a jute baron. She liked big-game hunting and thought she could find fun and glamour in film-making. The three of them formed British National Films Ltd in 1934.

Their first film was “Turn of the Tide” in 1935 but Rank was furious at its distribution as a second feature, losing some £12,000. Deeply angry he determined to investigate distribution, exhibition and production facilities himself. Enter Charles Boot, a wealthy Sheffield building tycoon also drawn into the world of film and who bought Heatherden Hall, a lavish mansion in Iver Heath, Buckinghamshire, with a view to establishing a studio.

Rank and Lady Yule joined with Boot to create Pinewood Studios Ltd at the hall as Britain sought to break the hold that Hollywood had on the nation’s film industry. The Pinewood foundation stone was laid in December 1935 and a new stage was completed every three weeks. The studio cost more than £1 million to build and opened on September 30, 1936.

That year saw the setting up of the The General Cinema Finance Corporation (GCFC), chaired by Lord (Wyndham) Portal, a paper magnate, and with J. Arthur Rank on the board of directors. Thus the British film industry had a potential powerhouse led by two men whose main business interests were paper and flour. Rank now had a finance and production company in place and GCFC joined with Charles Moss Woolf, a leading name in distribution.

It was Woolf’s secretary who thought up the “man and gong” logo. Carl Dane was the first Gongman, followed by Bombardier Billy Wells, Phil Nieman, Ken Richmond and (an unused) Martin Grace. Curiously, Dane struck the gong three times but his successors struck it only twice (and at The Budapest Times we are absolutely interested in such trivia). The golden gong would grace all Rank’s future films through to the company’s last in 1997.

In 1937, as Owen recounts, J. Arthur Rank, the millionaire milliner, consolidated “his not insignificant film industry interests in one company, The Rank Organisation. It was to become the greatest of all the British film companies”. Indeed, by 1942, namely within nine years, he had advanced from renting projectors at church Sunday schools to becoming Britain’s most powerful and influential film mogul. This empire consisted of studios at Pinewood, Denham, Islington and Shepherds Bush, 600 cinemas and he now had distribution.

The book tells us that while Rank concentrated on building his powerful organisation, he never forgot why he had entered the business in the first place. He formed GHW Productions with two partners to produce films with a religious message and boasting high production values. He threw open the doors of Pinewood to make them and pledged to supply new projectors to churches so that they could show the films.

Not everything was successful. Four divisions – to make cartoons, documentaries. B-pictures amd children’s films– were created but ultimately didn’t make money and were wound up.

Anyway, while the business dealings of rich men and women are all very well, and Owen is very thorough, it’s time we had some good stories about the films and their stars, and they duly arrive. Norman Wisdom met Marilyn Monroe, making her only British film, in a corridor and she kissed him “smack on the gob” after he told her it was his last day filming. Rank had given him a seven-year deal but didn’t know what to do with him, and it was more than a year before he made what would be the first of a dozen successful laugh-out-louds for them.

In “Reach for the Sky” a soldier said “bloody” and the censor asked, unsuccessfully, for a change to “ruddy”. “Campbell’s Kingdom”, set in Canada, had to be filmed in Italy with cotton wool for snow that then had to be sprayed green for spring. The film premiered in London, attended by the Canadian High Commissioner and his wife, and they squeezed hands when mistakenly recognising Lake Louise in Alberta where they had honeymooned.

For “Across the Bridge” avid Method actor Rod Steiger ran round the stage before shots, with Bernard Lee shaking his head and asking, “Silly bugger. Why can’t he just act?”. Donald Sinden quickly signed for a three-month shoot in the Greek islands but budget problems changed this to the Channel Islands and then to even-less-exotic Tilbury docks in London.

“The One That Got Away” would be the first film post-war with a German hero, and Hardy Kruger was cast. When a journalist asked if he had been a Nazi he said “Yes”, so the press boycotted him and the film. For another war film, the dramatic “Carve Her Name With Pride”, Virginia McKenna learned parachute jumping, judo and how to fire a sten gun.

Arthur Rank, philanthropist, was ennobled in 1957 for his services to the British film industry, becoming the First Baron Rank of Sutton Scotney, in the County of Southampton. In 1958 Queen Elizabeth and 12-year-old Prince Charles came to Pinewood without any entourage or bodyguards and watched filming of “Sink the Bismarck!” in the studio tank. She accepted a cup of tea provided no fuss was made and sat in the director’s chair to drink it.

The flour and film mogul Lord J. Arthur Rank died at Winchester, Hampshire, on March 29, 1972 aged 83. He had been Managing Director/Chief Executive from the beginning in 1932 until 1952, and was Chairman from 1952 to 1962, then becoming Life President. Rank Film Distributors oversaw the release of more than 700 productions, ending in 1997.

Rank had continually expanded way beyond films and its divisions included photographic equipment, laboratory equipment, radios, record players, theatres, clubs, ballrooms, bowling centres, motor inns, motorway services, television, office copiers, bingo, pubs and more.

There were falling profits and rising debt. “… one can’t help but think what devout Methodist J. Arthur Rank would make of his once great film empire having been carved up and sold off, standing today only as a gambling business?” Owen asked in 2021. The author is meticulous in documenting the changing fortunes, though for this reader the sections about the actual films make for greater reading than all the buying and selling. Still, give that man a gong.

Source link