-

An earthquake just off California’s coast poses dire tsunami risk for many communities - 12 mins ago

-

Iranian rapper Tataloo once supported a hard-line presidential candidate. Now he faces execution - 28 mins ago

-

Mom Captures Moment With Toddler, Just Days Later She’ll Be Gone - 36 mins ago

-

Last Night in Baseball: Francisco Lindor hits two-run double on broken toe - 48 mins ago

-

How ‘Cali’ became a slur among Vietnam’s growing army of nationalists - 52 mins ago

-

Scottie Scheffler Tweaks Tour Schedule with Major Ramifications - about 1 hour ago

-

Why were so many Thai farmers among the hostages held by Hamas? - about 1 hour ago

-

Will the Santa Cruz Wharf be rebuilt after it broke apart? - 2 hours ago

-

Braves vs. Giants Highlights | MLB on FOX - 2 hours ago

-

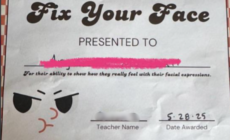

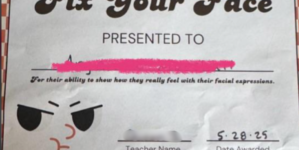

Teacher’s Award for Girl in Seventh Grade Sparks Debate: ‘Poor Kiddo’ - 2 hours ago

Auschwitz survivor returns to brave a harrowing past

Ruth was born Renee Friedman to a Czechoslovakian Jewish family that included doctors and rabbis. The Friedmans, she said, also owned a wholesale liquor business and ran a soup kitchen for those in need.

As World War II raged in the open, Nazi Germany secretly plotted to kill every European Jew, and the Third Reich’s genocide eventually reached the Friedmans.

They lost their business, then their home. And in May 1944 they were torn from each other, some forever.

Cohen’s mother, Bertha, her little brother, Ari, and her cousins Estee Haber, 9, and Leo Haber, 11, were all murdered along with Cohen’s grandmother and dozens more family members.

Cohen says her family had adopted the Haber cousins “to save from Slovakia, because it was important just to my parents, and then they came with us and got killed before their parents got killed.”

Cohen was not held captive in the Auschwitz I part of the extermination complex where her Tuesday tour began. But she believes her father spent time there. She saw him through a fence once at the nearby Auschwitz II-Birkenau camp, where she was imprisoned just over a mile away.

“I know he carried blankets … I guess to the crematoria or someplace, and that was in July.”

The Nazis tried to cover up their crimes, robbing survivors like Cohen of the details of loved ones’ final hours.

“There are many things I blacked out completely,” said Cohen. But walking through Auschwitz for the first time since her May 1945 liberation from another Nazi concentration camp, she described other memories vividly.

Cohen spent most of the roughly six-hour tour walking, eschewing first a wheelchair and then an insulated golf cart. Often, she walked without any assistance. There was only one place she specifically asked to see: Sector 2, Section C, Block 30.

“Six of us slept this way. Six of us slept that way. So there were 12 in one little area,” Cohen said while standing in the ruins of her former barrack, where a brick chimney still stands. The field was filled with chimneys.

She said the bunk beds were just wooden planks; the 11 other women in her area shared one space without barriers between them. Cohen’s older sister, Teresa, slept next to her every night.

“I’m sure, I’m sure, that it saved my life,” she said.

She asked her daughter, Barbara Cohen, to take a photo of her at the site: a 94-year-old Holocaust survivor posing with a smile at the Nazis’ largest extermination camp, where roughly 1.1 million people were murdered — roughly 90% of whom were Jewish, like Cohen’s family.

“I’m fine. I’m here and I’m here and I’m here. And Hitler lost,” she said.

Eventually, Cohen, her sister and their father were transferred to other concentration camps, liberated and reunited. They built a new life in America without so many loved ones.

Vowing to stop history from repeating itself, Cohen, who now lives in North Bethesda, Maryland, volunteers at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s “Survivors Desk,” sharing her story with visitors. But the world feels different to her today, with antisemitism surging.

“Antisemitism is changing. Racism is changing. Racism in all forms, as well as antisemitism, and it’s frightening, and that’s what has to be fought,” she warned, later adding: “The world seems to be getting worse rather than better. Nobody, nobody is remembering what happened.”

So Ruth Cohen decided she needed to return to the place that took so much and so many from her family and countless others.

“I have to be a witness to the world that I went through, the horrors. I survived. I made a life. I have children, wonderful children, who are going to carry not my legacy, but my history,” Cohen said.

That history brought Barbara Cohen to tears on Tuesday when she found her grandmother Bertha in the exhibit’s book of names.

“It’s just so real. I mean, my grandmother is part of me. I have her name and I can look at the buildings and I can look around me and see the horrors that obviously everybody lived through, but seeing her name, it’s her,” she said.

After hours of touring, giving testimony and praying for those who perished, Ruth Cohen offered advice for us all to prevent future genocide and the dehumanization of any group of people.

“I could say it in one word: love. … Love will never permit something like this to happen,” she said. “Hate might.”

Source link