-

Mets vs. Brewers Highlights | MLB on FOX - 7 mins ago

-

Dallas Housing Market Turns, Number of Homes for Sale Go ‘Through the Roof’ - 39 mins ago

-

Athletics vs. Orioles Highlights | MLB on FOX - 50 mins ago

-

Aston Martin Insider Shares ‘Fascinating’ 2026 Car Data After Adrian Newey Arrival - about 1 hour ago

-

Guardians vs. White Sox Highlights | MLB on FOX - 2 hours ago

-

Fifth Person in Florida Dies of Flesh-Eating Bacteria: What to Know - 2 hours ago

-

Marlins vs. Braves Game 2 Highlights | MLB on FOX - 2 hours ago

-

Why U.S. politicians care about Britain’s age verification law - 2 hours ago

-

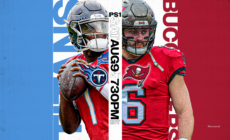

How to Watch Titans vs Buccaneers: Live Stream NFL Preseason, TV Channel - 3 hours ago

-

Phillies vs. Rangers Highlights | MLB on FOX - 3 hours ago

Evil beyond measure, he still cheated justice

The rout of the “1000-Year Reich” saw top Nazis killing themselves or fleeing retribution, or dangling from a noose. Adolf Eichmann was caught in Argentina in 1960 and executed in Israel. Josef Mengele was a fugitive in South America for 34 years until he drowned in Brazil in 1979 and was buried under a false name until 1985. Only then was the truth discovered.

The degenerate doctor’s atrocities made him the world’s most wanted man. When cattle trucks crammed with dead and living Jews and others arrived at Auschwitz concentration camp, Mengele personally sent thousands for death in the gas chambers and chose those he wanted for torture as human laboratory rats in his “medical” experiments.

Those who survived wanted him found before he died in his own bed, to know which substances he had injected into them, the blood transfusions that did not match, the drops in eyes to see if the iris changed colour, the spinal injections and so on, causing death, severe headaches, fever and nausea. He collected fetuses, eyeballs and other body parts. Apart from massacres, there were casually wanton acts of instant murder when he was angry.

SS-Hauptsturmführer (Captain) Mengele’s cruelty was beyond measure, with nil remorse. He “specialised” in twins, had pregnant women killed and threw a new-born baby into a fire in a fit of rage, an act hard to believe but documented in several first-hand accounts, Anton says.

And his death while enjoying the sea one summer day robbed everyone – the authorities, the Nazi hunters and the victims – of justice. Letters he left behind showed he enjoyed life in South America. The man loved his friends, travelled to the beach and countryside, went to waterfalls, admired the plants in the rich Atlantic Forest, tended his garden, went to barbecues, read his books and walked his dogs. He liked Brazilian soap operas on television. To the two children of the Bossert family that sheltered him in Brazil he was “Uncle Peter”.

Betina Anton’s fascinating book had its genesis in 1985 with one of her earliest childhood memories. As a 6-year-old kindergarten pupil she saw her teacher Liselotte Bossert, an Austrian expatriate, being apprehended by Brazilian authorities for allegedly using false documents to bury Mengele under the guise of Wolfgang Gerhard, the name on his false ID.

The school was a Germanic island in São Paulo and the children called Bossert “tante”, the German equivalent of “aunt”, rather than”aunt” itself, which was commonly used by young schoolchildren in Brazil. Bossert spoke a mix of Portuguese and German.

When she simply disappeared one day and was replaced, the child Anton realised that all the adults were saying the name Mengele, and while she didn’t know who he was she did realise that he was someone very bad. The young girl understood that the teacher had done something wrong. She says the parents were incredulous when the scandal broke.

Anton was born in São Paulo and since childhood has been connected with the German community there. She attended a German school and a Lutheran church, and her father worked for a German multinational company. Everyone she knew spoke German and Portuguese, and knew someone who had fought on the German side in the war, but not Nazi criminals. Many people were shocked to realise that Mengele had lived in São Paulo.

Today she has been a journalist in Brazil for more than 20 years and decided it was time to dig into the story of her teacher and the fugitive Nazi. Her starting point was Liselotte Bossert, to talk to her first-hand. But this was three decades-plus later and it took some months to find out that she was still alive, now 90 years old.

Bossert wasn’t answering her phone, so Anton went to her house and introduced herself as a former student now writing a book about Mengele from the German community’s perspective. The old lady would only come out to the gate and said she didn’t want to talk about Mengele, but then did so in a jumbled and sinister way, saying it was dangerous.

She began talking of mysterious people in the background who couldn’t be crossed, and the involvement of money. Anton didn’t know who Bossert was associated with and was so scared by the veiled and direct threats that she even thought of giving up writing the book.

Could Bossert be part of a Nazi network or something else entirely? She said she had never been tempted by the big rewards on offer into giving him away. The total had been almost $3.4 million, the largest sum ever offered to catch a criminal.

Fortunately for our understanding, Anton continued to write, and it is a marvellous account of all aspects of the Mengele case. His family lived in Günzburg, a small town in Bavaria, and his father Karl was a bourgeois businessman who owned an agricultural machinery factory. Family money would find its way to the fugitive Mengele in South America.

The son didn’t want to go into the family business and attended the University of Munich, gaining doctorates in anthropology and medicine. In January 1937 he joined the Nazi Party, having developed a deep ideological affinity on the issue of race. As an expert on genetics, Mengele became a racial examiner and began work at Auschwitz in May 1943.

He fled as the Soviet Red Army approached, taking his notes. These have never been found. In the post-war chaos there were eight million Nazis in Germany and Mengele escaped the net by using false names and working on a farm in the village of Mangolding for almost three years. With the support of his wealthy family and a Red Cross passport in the name Helmut Gregor he joned a “ratline” escape route to South America.

This offered a guide, clandestine accommodation and false documents at each stop. He left Bavaria for Austria, crossed through the town of Brenner into Italy, travelled to Genoa and on May 26, 1949 boarded the ship North King for a new life in Argentina where President Juan Domingo Péron welcomed fugitives from the Third Reich with open arms. Nazi escapees easily blended in with the many European immigrants in Buenos Aires.

Mengele settled, married in Uruguay and became a homeowner and a carpenter with his own company in Argentina. He even lived under his own name and visited Switzerland in 1956. The hunt for Nazis waxed and waned, but in 1959, 10 men of the Einsatzkommando death squads were jailed in the first major trial of mass extermination crimes in a German court, and the Central Office for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes was set up in Germany.

“Finally, German justice was interested in finding out what had happened in the largest Nazi extermination camp,” Anton writes. These revelations led to arrest warrents being issued and Mengel’s extradition was sought. Eichmann, a major organiser of the Holocaust, was caught by Israeli agents in Argentina, smuggled to Israel, tried and hanged.

Mengele fled from the Mossad agents and Nazi hunters to Paraguay then Brazil. Gitta and Geza Stammer, a Hungarian imigrant couple, were the first people to protect him in Brazil. Here he created his “tropical Bavaria”’, a place where he could speak German and maintain his customs, beliefs, friends and connections to his homeland. And in a pleasant climate.

But the strong sea pulled him out and drowned him. Bossert was found guilty of ideological falsehood for the fake burial but the sentence was overturned on appeal under the statute of limitations. Mengele’s exhumed body was identified beyond doubt. His bones lay forgotten in the Forensic Medical Institute in São Paulo but since 2017 they have been used by students.

At Auschwitz, Mengele sometimes gave sweets to the wretched children and he set up a phony kindergarten, earning slight regard as an “angel”, but it was all for show. To history he is the “angel of death”. “How,” Anton asks in conclusion to her exemplary account, “could a criminal of this magnitude and his supporters go completely unpunished in Brazil?”

Source link