-

How Did Dillon Gabriel Do in His First Start With Browns? - 42 mins ago

-

Derek Jeter: Cowboys’ Dak Prescott Needs To Win To ‘Change The Narrative’ - 48 mins ago

-

‘Golden Bachelor’ alum Gerry Turner engaged months after Theresa Nist divorce - about 1 hour ago

-

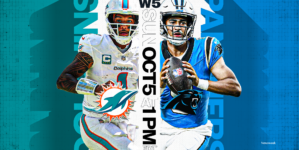

How to Watch Dolphins vs Panthers: Live Stream NFL Week 5, TV Channel - about 1 hour ago

-

Bills’ Josh Allen, Eagles’ Nick Sirianni Lead: Who Has It Better Than them? | FOX NFL Sunday - 2 hours ago

-

Small earthquake cluster hits near Big Bear Lake in San Bernardino County - 2 hours ago

-

Dyan Cannon, 88, clarifies viral ‘friends with benefits’ misunderstanding - 2 hours ago

-

Caesars Sportsbook Promo Code NEWSWK20X: Claim Top NFL Week 5 Sign-Up Bonus - 2 hours ago

-

'These games come down to one or two plays' — Alex Rodriguez on Mariners Game 1 loss to Tigers - 2 hours ago

-

Zac Brown engaged to Kendra Scott, plans to blend their families together - 3 hours ago

Made in China? How an iconic lion made its way to Venice

For centuries, an iconic winged lion has perched above Venice, a symbol of the “Floating City” that millions of tourists have passed under in St. Mark’s Square.

But scientists now believe that this ancient emblem of the Italian city may in fact have origins a world away.

A study released Thursday found evidence that the statue may have been partially made in China and arrived in northern Italy after a long journey across the medieval Silk Road that may have involved the father of the explorer Marco Polo and the court of the Mongol emperor Kublai Khan.

Historical documents confirm the statue was in Venice by the late 13th century, but its history before that remains murky.

How the lion made its way to Venice — an economic powerhouse in the medieval world owing to its strategic position close to Europe and the Byzantine Empire — has long been a mystery.

It was assumed by experts that the statue may have come from ancient Persia or Syria.

By studying copper isotopes taken from samples of the statue, scientists were able to identify that the metal originated from the Yangtze River in eastern-central China, more than 8,000 miles away from where it now stands.

Their findings were published in the archeology journal Antiquity.

“It’s a rather extraordinary discovery,” Hannah Skoda, associate professor of medieval history at the University of Oxford, told NBC News.

“At the same time it is indicative of the sheer extent and intensity of global trading networks, even in this really early period,” which would have made the long journey from China to Italy via the Silk Road possible all those centuries ago,” Skoda, who was not involved in the study, said in a phone interview.

The study’s conclusion “is striking — though perhaps not quite as improbable as it might sound,” said Peter Frankopan, professor of global history at Oxford and author of “The Silk Roads: A New History of the World.”

“Discoveries like this are not unusual once you start to look carefully at the materials, the motifs and the methods that shaped the cities we think we know,” he said by email.

The statue may not even be a lion at all, the study suggests.

Researchers argue that the figure closely mirrors tomb guardians from the Tang dynasty, which ruled from the 6th to 9th centuries during China’s golden age. These ancient sculptures were known as “zhenmushou” and share similar features with the Venice statue such as the position of the ears and the distinctive “bulbous nose,” according to the study.

There are no written records telling us where the statue that now looks down from a Piazzetta column in St. Mark’s came from. The only historical document mentioning it dates to 1293, and researchers have long presumed that the statue had a rich history before it made its way to Venice.

Scientists still don’t have a firm grasp on how exactly the statue traversed such great distances across multiple continents all those years ago. However, the study suggests that Niccolo and Maffeo Polo, Marco Polo’s father and uncle, might have discovered the original statue in the 13th century while visiting the court of Kublai Khan in what is now Beijing.

As traveling merchants, they would have then transported the statue back to their home city of Venice along the famed Silk Road.

Pointing to the fact that the city had not long ago adopted the lion as its emblem, the study suggested that the Polo brothers may have seen a Chinese figure and had the “brazen idea of readapting the sculpture into a plausible (when viewed from afar) Winged Lion.”

While not enough evidence exists to be sure of this rumored route, experts say the statue’s eastern origins underscore Venice’s longstanding global prowess.

As with so many great trading centers in history, Frankopan said, “the city’s capacity to absorb and adapt outside influences — from Byzantine mosaics to Egyptian porphyry … is what gave it dynamism and resilience.”

In such a global city, he adds, “a Tang dynasty lion fits right in.”

Source link