-

Cowboys Promise Change After Blowout Loss to Broncos - 27 mins ago

-

Favorite ‘Dogs: Back Vanderbilt at Texas, Falcons to Rebound at Patriots - 38 mins ago

-

Slain deputy leaves behind young daughter, pregnant wife. ‘He was a wonderful father’ - about 1 hour ago

-

Donald Trump’s Granddaughter Kai Set for ‘Dream’ LPGA Debut: What to Know - about 1 hour ago

-

From Freeman to Mazeroski: Every Walk-Off Home Run in World Series History - about 1 hour ago

-

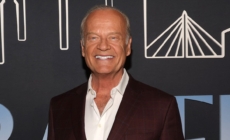

Kelsey Grammer welcomes eighth child, son Christopher with wife Kayte - about 1 hour ago

-

PayPal signs deal with OpenAI to embed payment system into ChatGPT - 2 hours ago

-

Santa Monica eyes bold turnaround plan amid financial troubles - 2 hours ago

-

Couple Saves Kitten From the Highway—Then Her Luck Drastically Changes - 2 hours ago

-

Government Keeps Ban on Ukrainian Imports - 2 hours ago

Peeping Tom made it past the censors and into renown

Three years after Alfred Hitchcock died in 1980, five of the best of his 53 films were taken out of his vault for re-release in cinemas, hardly having been seen since their release other than the odd television broadcast. They were “Rope”, made in 1948, “Rear Window” from 1954, “The Trouble With Harry” from 1955, “Vertigo” from 1958 and “The Man Who Knew Too Much” from 1956. I cosied up in a Sydney, Australia, cinema to watch the whole bunch.

The studios owned all Hitchcock’s films except these five that were his alone. His agent would offer only “Private reasons” as to why the director was so adamant about locking them away. They came to be known as the “Forbidden Five”. But now in 1983 it looked like time to revive them. They belonged on the big screen, not blink-and-you-miss-it on TV.

James Stewart starred in four of the five and as he said, while for many people “Vertigo” is the ultimate thriller, “Rear Window” was his own favourite, being Hitchcock at his best. Jennifer O’Callaghan, a Canadian freelance writer and journalist, offers a detailed account of this film that also featured Grace Kelly and has just passed its 70th anniversary.

All American films at the time faced the big threat to cinematic creativity of the Hays Code, a set of strict guidelines implemented by the industry in 1934 that barred profanity, nudity, sex and graphic violence. (Toilets, double beds, long kisses, safe-cracking and “raspberries” were among other no-nos). Also, Hollywood was going through the communist witch-hunt initiated by Senator Joseph McCarthy, resulting in some of the best talent being blacklisted.

So the industry felt a sense of doom. But when Hitchcock saw a film treatment for “Rear Window” in 1953 he knew it had to be made, even if its voyeuristic nature might raise moral objections at such a conservative time. Adapted from mystery writer Cornell Woolrich’s short story “It Had To Be Murder”, it would also be innovative, mostly set in a shabby, dark room.

Stewart would play world-travelling photographer L.B. Jeffries, Jeff to his fiancée, a man of action who has been laid up with a broken leg and a heavy plaster cast right up to his hip. He is stuck in a wheelchair and passes his long days and nights shamelessly using binoculars and a zoom lens to spy on his neighbours across the courtyard. It is a muggy summer in New York and all windows and blinds are open. We, the audience, peep and perspire with him.

O’Callaghan tells of the challenges Hitchcock faced. One, sculpting a script to breathe humanity into a noir short story that lacked warmth and romance. Solution: John Michael Hayes, the clever wordsmith who pulled it all together. Two, finding an actress who could hold her own against Stewart, a woman with strength of conviction but also the picture of femininity, ethereal but almost out of this world. Solution: Grace Kelly, the glacial blonde.

The single set itself would be as important as the stars, with audiences facing it for much of the 111-minute duration. O’Callaghan calls it a life-size dollhouse, 40 feet (12 metres) high and 85 feet long (26 metres), duplicating a Greenwich Village terra-cotta apartment building with a grassy courtyard and changing views of the New York skyline, depending on the hour.

Building it ran from October 12 to November 13, 1953 and the size of the set necessitated excavating the soundstage floor 30 feet (9 metres). It cost $9000 to design and $72,000 to build, an unheard-of amount and 25 percent of the entire budget. The whole set had a sophisticated drainage system for the rain scene and ingenious wiring for the complex lighting of day and night scenes in both the exterior of the courtyard and interior of the apartments. It was the most elaborate set since DeMille’s “Samson and Delilah” in 1949.

But then the Production Code Administration (PCA) decided to object to the script’s “sexual suggestiveness” and “voyeuristic quality”. After all, here was a Peeping Tom spying on a young, scantily clad woman over the way, plus he suspects a gruesome murder (was there?).

The whole film was in danger of collapse until the problem was solved by the rare feat of persuading the PCA staff to visit Paramount’s Stage 18 to see the set. They were persuaded that the “objectionable” scenes of a sexy miss in her undies and an implied bloody slaying and dismemberment would be mitigated by clever use of distance and camera angles.

Stewart/Jeffries was captivated by not only the pretty girl (dubbed Miss Torso) but also a pianist struggling to compose, a sleeping couple on a fire escape (few working-class people had air-conditioners), a sculptress, a depressed spinster (Miss Lonely Heart) and a bride and groom busy on their honeymoon, thus keeping their shades firmly closed.

O’Callaghan tells how studio photographers were sent to scout New York buildings from all angles in all types of light, with the courtyard of 125 Christopher Street in the West Village then chosen for replication at Paramount. The building is still there. For authenticity, Hitchcock’s film also referred to notable New York spots the 21 Club and the Albert Hotel.

Great care was taken with casting, and Raymond Burr, Thelma Ritter and Cornell Woolrich landed the roles as the suspected murderer, the nurse and the dubious cop, respectively. O’Callaghan says their selection was no easy feat, as they would be just as imperative to the plot as Stewart and Kelly. Surprsingly, we read that Ritter received the highest salary of all the cast, $25,694. She injects important comic relief into a tension-laden story, predicting trouble: “The New York State sentence for a Peeping Tom is six months in the workhouse.”

Hitchcock spent much time with leading costume designer Edith Head on Kelly’s look. He fretted over her negligee and quietly pulled Head aside to suggest falsies for a bustier look. Kelly refused, and she and Head made only a few changes in costume construction and posture, fooling the unknowing Hitchcock into thinking Kelly had been padded.

Apart from declining falsies Kelly did her own stunt, climbing a fire escape in high heels to look for evidence. Hitchcock made his traditional cameo, winding the clock at the fireplace in the songwriter’s apartment at the 26-minute mark. In a film focused on looking into people’s lives, he stares out of the window and back at the audience, almost directly at the camera.

An interesting revelation is that during production the beginning of the script was chopped off and a new ending devised at the last moment. The film had been going to open with a phone call from an insurance office to Jeffries, but it was deemed better to show him receiving the call and thus keep the entire action on the one set. And at the finale, when the killer (he was) pushed Jeffries out the window, the idea arose to give him two broken legs.

O’Callaghan offers many tidbits for we amateur cineastes, such as how certain film-makers, including Hitchcock, tricked the censors by planting sacrificial red flags in rough-cut submissions that could be cut while distracting from contentious material they wanted kept.

“Rear Window” premiered at the Academy Theater in Pasadena on August 1, 1954 to a test audience, with varied and unpredictable comment cards. After the Hollywood premiere the film came in fifth in 1954 for revenue. But at the March 1955 Academy Awards it failed to win Best Picture or Best Director. O’Callaghan says it has grown in stature over time.

The author goes on to look at the eventual crumbling of the Hays Code and the whole studio system, plus “Rear Window” litigation, auctions, the ratings system, “remakes”, the role of Hitchcock’s wife Alma Reville and right up to how the film’s themes are reflected in today’s pop culture, in the dot.com world and even aiding female empowerment in the #MeToo age.

The hardback has 16 pages of photos, the paperback does not.

Source link