-

Spain vs. Portugal: UEFA Nations League Final updates, highlights - 16 mins ago

-

National Guard on Scene Following Los Angeles Protests: Police - 36 mins ago

-

Chris Pratt shows off dramatic transformation with fake mustache on set - 44 mins ago

-

A bright side to another loss? Why the USMNT feels good despite sloppy showing - 59 mins ago

-

A political lesson for L.A. from an unrestrained president - about 1 hour ago

-

Southern States Brace for Storms After Deadly System Saturday - about 1 hour ago

-

2025 Big Bets report: Two 7-figure bets land on Thunder to win NBA Finals - 2 hours ago

-

Zelensky Addresses ‘Complicated’ Aftermath of Oval Office Blowup With Trump - 2 hours ago

-

Former Villanova coach Jay Wright not interested in Knicks head coach job - 2 hours ago

-

House Speaker Says Deploying Marines in Los Angeles Not ‘Heavy-Handed’ - 3 hours ago

Spike Lee celebrates Malcolm X’s enduring legacy on the 100th anniversary of his birth

Brooklyn, for filmmaker Spike Lee, is what Harlem was for Malcolm X: a community pulpit from which to do his life’s work and muse on America. For Malcolm, it was routinely a gritty street corner transformed into a pop-up rally, the tools of his trade the fiery speeches, the Nation of Islam newspaper, his unapologetic media interviews and his uncanny ability to mix and remix deft intellectual observations, including the most uncomfortable and harsh, with the raw poetry of the people. For Lee, it is his provocative storytelling transformed into town hall meetings on this country’s social ills, the tools of his trade the hot-button movies, the ever-changing façade of his red-brick multistory headquarters on South Elliott Place in the heart of the Fort Greene neighborhood, espousing one cause or another, one leader or another, his unapologetic media interviews and his uncanny ability to mix and remix deft intellectual observations, including the most uncomfortable and harsh, with the raw poetry of the people.

Sam Norval

From the prescient moment when Lee’s late mother Jacqueline, a teacher of the arts and Black literature, had him read The Autobiography of Malcolm X as a bony, baby-faced youth, Lee has proclaimed, habitually, that it is the most important piece of writing he has ever come across. President Barack Obama has said similar. But what is it about Malcolm X, a Black man, and his rags-to-revolution story, that keeps him ever-present as we mark, in 2025, the 100th anniversary of his birth on May 19, 1925, and more than 30 years since Lee’s ambitious screen narrative?

Or rather, why does Malcolm—a widely debated man, one who is loved and hated, revered but also feared, universally studied yet often wildly misunderstood—still linger in the global public imagination?

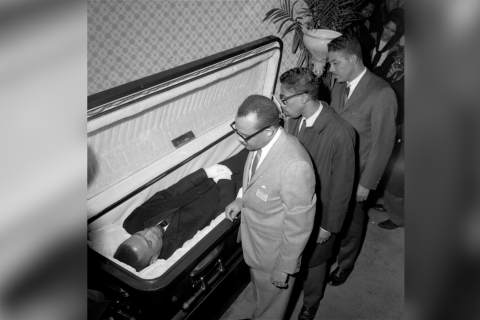

AP Photo, File

Perhaps at least portions of the answers rest with Lee, and his landmark 1992 cinematic collage Malcolm X. It begins with the infamous and horrific videotaped beating, by Los Angeles police, of motorist Rodney King, in 1991. The film was released at the conclusion of 12 years of Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush running the government, and cutbacks to social programs that disproportionately affected the marginalized, including Black Americans. Conservative adversaries of affirmative action were chosen to lead the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the Commission on Civil Rights, while severely reducing their staffing and funding. Furthermore, spending reductions affected Medicaid, food stamps, school lunch and job training programs that afforded critical support to Black households. Malcolm X came on the heels of these measures as the crack and AIDS pandemics, correspondingly, decimated many Black families and communities, as depicted in another one of Lee’s movies, Jungle Fever, in 1991.

In 2020, near the end of Donald Trump’s first term as president, we had the cellphone camera audiovisual of George Floyd’s slaying at the hands of the Minneapolis police. And with this second Trump term, there have already been massive pushbacks on diversity, equity and inclusion.

As Lee contemplates America of the Reagan years with MAGA of today, he leans forward, adjusts his multicolored bracelets and says: “Ain’t that much changed, particularly with this new world we live in.”

David Dee Delgado/Getty

‘That Film Made an Impact’

Malcolm X was a watershed for American cinema. As Spike tells it: “A lot of people have come up to me and said that film made them read. [Film director] Ryan Coogler told me his father took him to see Malcolm X when he was 6 years old. Sat on his knee. I’m not sure what you could comprehend at 6 years old, but he said that film made an impact.”

Largo International NV/Getty

Lee was 35 years old when Malcolm X debuted. He had battled numerous obstacles to get it made. He fought to make it an epic running at three-plus hours when Warner Brothers wanted it shortened to 120 minutes instead. He fought to have Malcolm’s mind-altering pilgrimage to Mecca, the holiest of journeys for any Muslim, shot on location. And when the producing studio would not disburse any more funds for his vision, Lee organized Black investors like Oprah Winfrey, Magic Johnson, Tracy Chapman and Michael Jordan to get it to the finish line. Lee persevered with Malcolm X because he felt it was part of his calling as a filmmaker, the mustard seed planted decades before when his mother instructed him to study Malcolm’s essence.

Fast forward 33 years and Lee, who turned 68 in March, remains as youthful as ever, despite the gray stubble on his chin—and as animated, too. During the interview, he wears a blue 1619 cap, denoting the year when captured and chained Africans were first brought to the U.S. to work as slaves for what would be 246 years.

“When I knew you were coming. I said, ‘I’m not wearing that Knicks hat today. I’m not wearing that Yankee with the interlocking NY.’ 1619,” he says, pointing at the numbers on his cap. “Our ancestors built this country—free labor—from can’t see in the morning, to can’t see at night. Our families torn apart, our ancestors raped, men and women.”

Sam Norval

Where Malcolm X regularly detailed the enslavement of Black people in his lectures, Lee christened his film production company 40 Acres and a Mule, from a perceived promise of reparations to formerly enslaved persons at the end of the Civil War. History pulses—like a parade of ancestors humming the blues in a museum—from every pore at 40 Acres: on the walls, along the stairwell, in the bathroom. Cinematic posters highlight classics by masters like Melvin Van Peebles and Martin Scorsese; multiple sports images, of Jackie Robinson, the Brooklyn Dodgers pioneer who became the first Black American to play Major League Baseball in the modern era, and of Spike’s beloved New York Knicks, including an oversized and slightly washed-out 1970s Madison Square Garden banner bestowed to Lee; a plethora of keepsakes and memorabilia from Lee’s 30-plus films; frozen-in-time visuals of boxing superstars like Jack Johnson, Joe Louis and Muhammad Ali; and, yes, there is a gigantic Malcolm X movie print, as well as a framed, signed letter from Nation of Islam head Louis Farrakhan from the early 1990s, simultaneously praising Lee’s effort and disapproving of impressionistic drawings of Malcolm’s former organization and its then leader, Elijah Muhammad.

From Detroit Red to the Nation of Islam

Malcolm X was born Malcolm Little, in Omaha, Nebraska, to parents who were followers of the Jamaican Black nationalist Marcus Garvey, whose largest movement was in the United States during the Jazz Age of the 1920s. Malcolm’s Georgia-born father, Earl, was a traveling preacher who was murdered by white racists for encouraging local Blacks to be self-sufficient, to know their history, to consider a return to Africa. Left with seven children to raise, Louise Little, Malcolm’s West Indies-born mother, an educated and proud woman, crumbled beneath the weight of probing social workers and poverty and wound up in a mental institution. Malcolm and his siblings were distributed, like sacks of food during the Great Depression, to various families—what we would call foster care. He went on to crawl the streets—in New York City, in Boston—using his nickname “Detroit Red” and engaging in a range of illegal activities, including gambling and selling drugs. That Malcolm would spend seven years in prison for burglary, where he would be introduced to The Nation of Islam, changing his path forever. But it was the next Malcolm, post-prison, who terrified white America, and none too few in Black America as well.

It was as if that Malcolm X—the “X” standing for the name Black folks lost when brought from Africa as enslaved people—unleashed a rebuttal on racism in America for an entire group with every fiber of his being. He called himself the angriest man in America, he grew into a star voice in the Nation of Islam, a media darling and a pariah, all at once. He married Betty Shabazz, would have six daughters—a set of twins born after his death; mentored heavyweight boxing champion-to-be Muhammad Ali; became the victim of internal jealousy due to his popularity as the national spokesperson for the NOI; made a major misstep with his words upon the assassination of President John F. Kennedy by uttering “the chickens coming home to roost,” after being warned by Elijah Muhammad to say nothing; and, embarrassingly, got kicked out of the NOI, allegedly, for disobeying Muhammad’s edict.

In the last months of his life, Malcolm would travel extensively through the Middle East and Africa and revamp his vision for humanity as a result of those excursions. Gone was what many felt was hate, replaced by compassion, empathy and an eagerness to work with any who were willing to work with him, for freedom, justice and equality. This is the Malcolm that many are least familiar with, the one who kept evolving until that fateful day. This is the Malcolm in the only photo which exists of him and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.—two men smiling cordially, shaking hands. “The final image before we go to end credits,” Lee says.

Universal History Archive/Getty

‘The Spirit of Malcolm Came Into Him’

Before those credits is the re-creation of Malcolm X’s assassination. He was killed at age 39 on Sunday, February 21, 1965, at the Audubon Ballroom in New York City. Lee still struggles to recount the filming of that tragic scene.

“The cast and crew, I mean, we were spiritually high, but we knew eventually we had to shoot the assassination scene, and that was when everybody’s spirit was at the lowest. Wow. And that was, that was not fun. It was part of what happened, and we weren’t gonna leave that out of the script, but it was rough.”

AP Photo/File

Denzel Washington’s performance as Malcolm X resonated with audiences and earned him an Oscar nomination for Best Actor. The manner in which he contorted his body during the varied stages of Malcolm’s life, the manner in which a single tear came down his face upon meeting Elijah Muhammad in the flesh—spiritual father and son, mentor and mentee, savior and the saved. The memory of that scene still gives Lee chills.

“I said, ‘Cut.’ And I walk up to Denzel. I’m looking at his eyes glazed over. I said, ‘Where’d that come from?’ He said, ‘Spike, I don’t know.’ But Denzel, he prepared for that role a year before we began the film. Denzel did the work, and the spirit of Malcolm came into him.”

Lee adds: “When we were doing that film, we weren’t seeing Denzel, we were seeing Malcolm.”

Largo International NV/Getty

It was the second time Washington and Lee had worked together, following 1990’s Mo’ Better Blues. He Got Game and Inside Man followed in 1998 and 2006, respectively. A fifth outing, the upcoming crime thriller Highest 2 Lowest—an English-language reinterpretation of Akira Kurosawa’s 1963 Japanese film High and Low—opens in theaters on August 22.

“No disrespect to any other actor, but I think Denzel is the greatest living actor today,” Lee says of his friend.

Though rough and troubled our times may be, Lee remains hopeful, possibly because he has witnessed so much, possibly because he, like Malcolm X, has been misunderstood, derided, called every name imaginable. But Lee has survived. He dotes on his wife, Tonya Lewis Lee; he views his daughter, Satchel, and son, Jackson, as more valuable to his legacy than his films.

At the glass table where Lee is doing the interview with Newsweek is a cup with an imprint of Radio Raheem’s rings from Do the Right Thing, arguably one of his masterpieces. On one hand the elongated ring says LOVE, on the other HATE. Lee reveals he came across those words together while a student at New York University film school when he saw a 1955 movie starring Robert Mitchum called The Night of the Hunter. Mitchum’s character had LOVE tattooed across the fingers of his right hand, HATE across the fingers of his left.

“It’s simple. Either you are a mindset of love, or a mindset of hate. If you’re the spirit of love, then you’re gonna act like it. If you ain’t, if you’re on the other side, then your actions will tell who you really are.”

Kevin Powell is a Grammy-nominated poet; human and civil rights activist; author of 16 books; journalist and director, co-writer and co-producer of the new documentary film when we free the world, which will hit streaming platforms this summer.

Source link