-

Blue Jays vs. Twins Highlights | MLB on FOX - 7 mins ago

-

Rory McIlroy’s Stunning Admission of ‘Concern’ for US Open - 39 mins ago

-

DC Defenders vs. St. Louis Battlehawks Highlights | United Football League - 50 mins ago

-

Retail trade rebounds: broad-based growth in food, non-food and fuel sales - about 1 hour ago

-

Viral Beauty Routines Are Damaging Tween and Teen Skin, Study Warns - about 1 hour ago

-

‘I gave it my all’: Ronaldo sheds tears of joy after Portugal’s Nations League win - 2 hours ago

-

NY Giants Star Issued Jaxson Dart an NFL Reality Check - 2 hours ago

-

NBA Finals Game 2 takeaways: Thunder bounce back to even series 1-1 - 2 hours ago

-

Packers QB Jordan Love Generating Buzz Ahead of 2025 Season - 3 hours ago

-

UFL Top 10 Plays from Conference Championships | United Football League - 3 hours ago

What Panamanians have to say about Trump’s threats to retake the canal

Panama’s control of the canal that bears its name should not be returned to the U.S. despite President Donald Trump’s calls of “we’re taking it back,” Panamanians say.

Although most people thought the matter was closed when Panama officially took control of canal operations from the U.S. in 1999, the issue reared its head during the republican candidate’s campaign when he suggested the engineering marvel that connects the Atlantic and Pacific oceans was being run by China and should return to U.S. control.

Trump repeated that claim in his inaugural speech this week, saying, “China is operating the Panama Canal,” and “we’re taking it back.” NBC News has learned Secretary of State Marco Rubio will visit Panama during a Latin-American and Caribbean tour that starts late next week.

Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, Panama’s President Jose Raul Mulino dismissed the notion as he and other Panamanian leaders tried to gain international support this week for keeping the canal under their nation’s authority.

Among those leaders is Jorge Luis Quijano, a former canal administrator, who insists Panamanians are running the waterway, not the Chinese. He also disputed Trump’s complaint that U.S. ships pay more to pass through the canal than other countries.

“A ship with a Panamanian flag pays as much as an American-flagged ship,” Quijano said, adding that rates are based on a vessel’s size, and large container ships may pay as much as $1.2 million to pass through the 51-mile waterway that cuts through the Isthmus of Panama.

Quijano said he started working at the canal in 1975 after graduating as an engineer from Lamar University in Beaumont, Texas, when the U.S. still controlled it. He said Americans were the supervisors when he started, but Panamanians eventually became the managers and “the Americans retired.”

“I saw the whole movie,” Quijano said jokingly about witnessing the transition over the 44 years he worked at the canal, eventually becoming vice president of operations and leading a reconstruction effort that expanded the channel’s capacity in 2016.

Humberto Arcia, 72, who lived two miles from the canal in the Chorrillo neighborhood as a child, said he will never forget the price Panamians paid for the right to run the canal in their own country.

The Hay-Bunau-Varilla treaty signed in 1903 gave the U.S. the right to build and manage the Panama Canal. Construction began in 1904 after a failed attempt by a French construction team to build the ambitious passage.

The massive project took the lives of more than 5,000 construction workers, 350 of them U.S. citizens, until its completion in 1914. Most of the workers were from Caribbean nations.

Panama’s relationship with the U.S. was marked by riots and demonstrations opposing American involvement in the Central American nation’s affairs and control over the canal.

In 1964, anti-American riots broke out in Panama because the Panamanian flag was not allowed to fly next to the U.S. flag at Balboa High School in the U.S.-controlled Canal Zone that was attended by American students, according to the U.S. National Archives. The Canal Zone was a 10-mile concession of the U.S. where canal employees and their families lived.

The protests escalated and students from multiple high schools outside the Canal Zone marched to its entrance, where at least 20 people were killed in clashes with the U.S. military, National Guard and Canal Zone Police during three days of riots. The protests are commemorated each year on Jan. 9, a national holiday, known as the Day of Martyrs.

Arcia, a retired banker and attorney, remembers hearing relatives of the students talk about their loss when he lived near the Canal. “Their suffering changed the lives of their families forever,” he said.

The riots were a turning point in Panama’s history, but it wasn’t until 1977 that President Jimmy Carter and the Panamanian military leader Omar Torrijos signed the Torrijos-Carter Treaty that would eventually lead to Panamanian oversight.

The Panama Canal Authority assumed full control on Dec. 31, 1999.

U.S. historian David McCullough wrote in his book “The Path Between the Seas”: “The fifty miles between the oceans were among the hardest ever won by human effort and ingenuity, and no statistics on tonnage or tolls can begin to convey the grandeur of what was accomplished. Primarily the canal is an expression of that old and noble desire to bridge the divide, to bring people together. It is a work of civilization.”

The Panama Canal was designated one of the seven wonders of the modern world in 1994.

Today, the canal is one of the U.S.’s most important trade routes and the top revenue source for Panama. The canal generates yearly revenues above $5 billion to the country’s coffers, according to the U.S. State Department.

The ships that pass through generate income, but the canal also attracts businesses that create jobs in industries such as logistics, insurance and banking, according to the Panama Canal Authority (ACP).

Panamanians said the canal is part of their national identity.

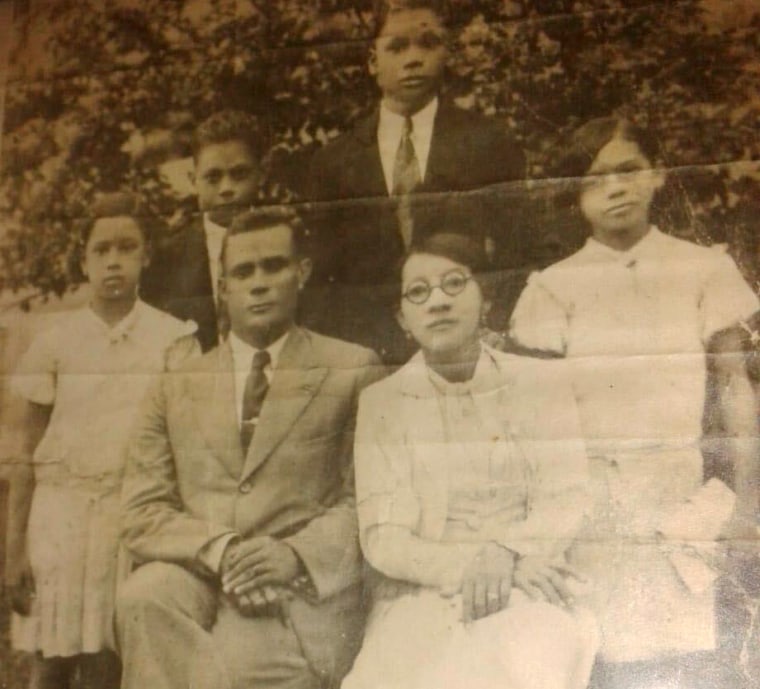

Panamanian business consultant Marjorie Miller said her great-grandfather, John Miller, moved to Panama from Jamaica to work at the canal. U.S. Census Bureau records show he lived in the American labor camp known as the Red Tank with other canal workers.

“I always knew how important the canal was to our country because of my ancestors,” she said. “The Panama Canal is Panama. It is our greatest asset.”

Miller said she is frustrated by comments posted by Panamanians on social media about how the U.S. could probably do a better job running the canal than Panama.

“The comments come from ignorance,” she said, adding that many younger people in her country lack the historical knowledge to understand the importance of the canal for the country.

Miller also said that Trump’s comments about China’s involvement in the canal’s operations may have arisen because Panama broke diplomatic relations with Taiwan in 2017 and established ties with China instead.

“We were friends one day, and now we are hearing, ‘We want your canal,’” she said. “That’s a big change when the U.S. is our greatest trading partner.”

A spokesperson for China’s foreign ministry, Mao Ning, said at a Wednesday news briefing that Trump’s comments about China and the canal are baseless.

“Panama’s sovereignty and independence are not negotiable, and the Panama Canal is not under direct or indirect control by any power,” Ning said. “China does not take part in managing or operating the canal. Never ever has China interfered. We respect Panama’s sovereignty over the Canal and recognize it as a permanently neutral international waterway.”

Quijano, the former vice president of operations, said he doubts the U.S. could easily run the canal because it takes 12 years of training for an engineer to learn the complicated system of locks and water elevators that route giant ships through the canal.

“If he thinks he is going to take it back and then we are going to run it for him, the answer is no,” he said. “All of us just need to respect the treaties and the sovereignty of nations.”

Arcia, who grew up near the canal, said Trump needs to change his tone toward Panama: “What we always want is a beautiful relationship of equality, not submission.”

Source link