-

Commentary: The state sets lofty goals in the name of a brighter future. What’s a vision and what’s a hallucination? - 26 mins ago

-

NFL Preseason Betting Odds, Picks For Dolphins-Bears, Saints-Chargers - 34 mins ago

-

Which 10 Players Have The Most Single-Game Rushing Yards in FBS History? - 43 mins ago

-

How might you reconfigure L.A. so it’s a sustainable home for everyone? - about 1 hour ago

-

DraftKings Promo Code: Get $200 Bonus For Sunday MLB, NFL Preseason Games - about 1 hour ago

-

Jaguars’ Cam Little Makes Unofficial NFL Record 70-Yard Field Goal vs. Steelers - about 1 hour ago

-

Hollywood takes a wrecking ball to Los Angeles - 2 hours ago

-

Mets Legend Named Option for Yankees to Replace Aaron Boone - 2 hours ago

-

Netanyahu says starvation claims in Gaza are exaggerated as backlash mounts over plans for new Israeli offensive - 2 hours ago

-

Fires and floods have plagued L.A. forever; brilliant marketing lured millions of newcomers anyway - 2 hours ago

Fires and floods have plagued L.A. forever; brilliant marketing lured millions of newcomers anyway

From the book “GOLDEN STATE: The Making of California” by Michael Hiltzik. Copyright © 2025 by Michael Hiltzik. Published on February 18, 2025, by Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Excerpted by permission.

The writer Morrow Mayo seldom minced words, especially when his subject was the gaudy, tawdry city where he made his home in the 1920s and 1930s.

“Los Angeles, it should be understood, is not a mere city,” he wrote. “On the contrary, it is, and has been since 1888, a commodity; something to be advertised and sold to the people of the United States like automobiles, cigarettes and mouth wash. … Here is a spirit of boost which has become a fetish, an obsession, a mania. Everything else is secondary to it.”

Los Angeles knows how to weather a crisis — or two or three. Angelenos are tapping into that resilience, striving to build a city for everyone.

Mayo’s acerbic book “Los Angeles” appeared in 1933, when the city was in its second decade as the dominant metropolis of California; in the 1920 census, its population had finally exceeded that of San Francisco, which had been the center of the state’s economic and political life since the Gold Rush and the granting of statehood.

That Los Angeles would someday overtake San Francisco in prominence was in some respects preordained. San Francisco is geographically constrained, perched at the end of a narrow peninsula like a fingernail, with water on three sides. Consequently, its population has never reached even 900,000.

Los Angeles lies nestled within a vast basin stretching from the Pacific Ocean to the San Gabriel and Santa Monica mountain ranges on the north and northwest, some 3½ million acres of mostly undeveloped territory capable, in the fullness of time, of supporting a population of more than 13 million.

An aerial view of Harbor Freeway construction at 42nd Street South, looking north toward the Civic Center, in 1957.

(USC/Corbis via Getty Images)

Yet seen from another perspective, nothing could be as surprising as the birth in that particular location of a gigantic, vigorous megalopolis.

The Los Angeles Basin is a place seemingly devoid of the resources needed to sustain life and commerce. For most of its history, it has had no reliable supply of water, no port. The best natural harbor in Southern California is San Diego’s, and the nearest shore is a 30-mile trek from the pueblo that the Spaniards of Mexico established as their civic seat early in the 19th century. Its rivers are dry gulches for most of the year; Mark Twain is said to have quipped that he once fell into a Southern California river and “come out all dusty.”

The Los Angeles that became the queen city of California did not grow naturally, but had to be “conjured into existence.” Almost everything that made it habitable needed to be imported. Its water came from a river valley 200 miles away and its electricity from a river canyon 300 miles to the east, brought to the city via systems that are titanic marvels of human engineering. It is wrong to think of the basin as a void to be filled up; better to view it as a gigantic canvas on which its settlers painted a new, transformative future for their state.

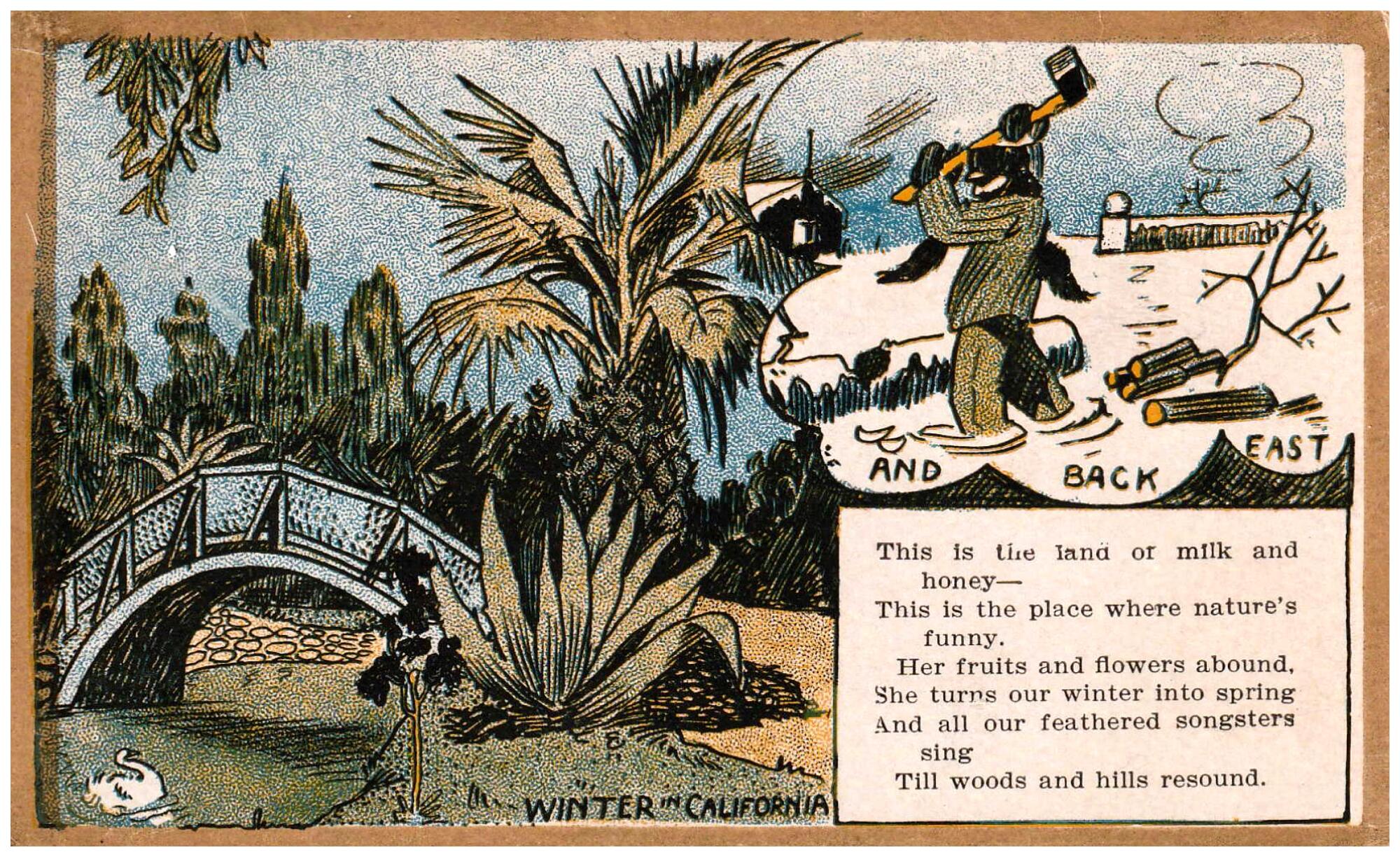

A postcard postmarked 1912 from the collection of Patt Morrison touts the mild winters of Southern California.

(Courtesy of Patt Morrison)

A history of natural catastrophes

For decades, the economy of the region stretching south of the Tehachapi range stagnated. In 1850, while San Francisco was basking in the stupendous influx of people and wealth produced by the Gold Rush, Los Angeles was still barely a village, with 1,610 inhabitants recorded in the 1850 census and “no newspaper, hospital, public school, college, library, Protestant church, factory, bank, or public utility of any kind.” One-third of its residents could neither read nor write.

With one exception, the Gold Rush left almost no trace of itself in the portion of California from Monterey south to the Mexican border. The exception was the Southern California cattle industry, which briefly prospered thanks to the gold miners’ demand for beef. Yet in time, the cattle ranchers fell victim to the emergent boom-and-bust pattern of the Southern California economy. Beef prices were driven so high by the surge in demand that Mexican ranchers flooded the market with livestock, eroding what had been a Southern California monopoly; by 1855, the competition had sent prices plummeting by 75%.

Then came a series of natural catastrophes, starting with punishing droughts in 1856 and 1860. They were followed perversely by torrential rains in 1861, which drowned hundreds of head. Yet another drought arrived in 1863, killing cattle by the tens of thousands; for years to come travelers in the south would be “often startled by coming suddenly on a veritable Golgotha, a place of skulls, the long horns standing out in defiant attitude, as if protecting the fleshless bones.”

Pitching the Southern California dream

The promotion of Southern California’s Mediterranean climate took hold in the first decade after the Gold Rush and continued into the new century. Travel writers praised the region’s moderate temperatures and lack of humidity — dry, but not too dry — and described its healthful effects as almost miraculous. “The diseases of children prevalent elsewhere are unknown here,” reported Charles Dudley Warner, the co-author with Mark Twain of the 1873 novel “The Gilded Age.” “They cut their teeth without risk, and cholera infantum never visits them. Diseases of the bowels are practically unknown. … Renal diseases are also wanting; disorders of the liver and kidneys, gout, and rheumatism, are not native. … These facts are derived from medical practice.”

A “Winter in California” postcard postmarked 1905 from the collection of Patt Morrison draws a sharp contrast between East and West Coast winters.

(Courtesy of Patt Morrison)

Ben C. Truman, an East Coast transplant, compiled the death rates from all causes in American cities for his 1885 book “Homes and Happiness in the Golden State of California” and found 37 deaths per thousand inhabitants in New Orleans; 24 in St. Louis, Boston and Chicago; and a mere 13 in Los Angeles. “Fevers and diseases of the malarial character carry off about half of mankind, and diseases of the respiratory organs one-fourth,” he wrote. “From such diseases many of the towns of California are remarkably free.”

The German-born journalist Charles Nordhoff wrote glowingly of the regional climate’s health-giving qualities for tuberculosis patients, describing it as the French Riviera’s equal, lacking only the deluxe hospitality infrastructure of that renowned gathering place of the rich: “You will not find … tasteful pleasure-grounds or large, finely-laid-out places. Nature has done much; man has not, so far, helped her.” If he was trying to alert resort developers to the existence of a blank slate to be written on for great profit, he could hardly have done better

A place to start anew

In 1887, some 120,000 passengers were brought into Los Angeles by the Southern Pacific railroad, while the Santa Fe served the region with as many as four passenger trains a day. Tourists jammed hotels and boardinghouses, but they were not the only newcomers. The steady rise of land values attracted fortune seekers eyeing the prospect of making a killing in real estate as well as families with the simpler ambition of making new lives in the West. Between 1880 and 1890 the city’s population nearly quintupled, from 11,000 to 50,000. Los Angeles “suddenly changed from a very old city to a very young one.” In 1890, more than three-fourths of its residents had lived in the city for fewer than four years.

Recounted travel writer H. Ellington Brook, “Everybody that could find an office went into the real-estate business … a crowd of speculators settled down upon Los Angeles like flies upon a bowl of sugar.” The railroads brought swarms of sharp operators who had already drained the Midwest of its potential for land fraud and detected on the West Coast a “golden opportunity of the fakir and humbug and the man with the past that he wanted forgotten,” a municipal historian wrote. Thus was born Southern California’s image as a place to start anew, especially among those with reason to shed memories of a previous life.

A postcard dated 1912, from Patt Morrison’s collection, shows the industry that built up along the L.A. River. A message on the back says that the river is dry in the summer and that “we have not had enough rain yet this year. It gets pretty well filled up in the rainy season.”

(Courtesy of Patt Morrison)

To a great extent, the boom in real estate values was based on fiction. Los Angeles still had almost no industry to sustain its growing population — indeed, virtually no economic activity at all other than real estate speculation. Promoters established new townsites on every patch of vacant land, building hotels and laying down concrete sidewalks and community halls: “A miniature city appeared, like a scene conjured up by Aladdin’s lamp, where a few months ago the jack-rabbit sported and the coyote howled,” Brook wrote.

The big boom

Climate, romantic mythology, the lure of real estate wealth — all these factors set the stage for the greatest boom of all. Nearly 1.5 million new residents moved into Southern California between 1920 and 1930, an influx that was labeled “the largest internal migration in the history of the American people,” and one that would not be exceeded until the postwar 1940s and 1950s. The explosive growth brought with it gimlet-eyed reassessments of what it had taken to bring Los Angeles to its newfound stature as reigning metropolis of the West.

Source link