-

Angels vs. Orioles Highlights | MLB on FOX - 5 mins ago

-

Topless Gwyneth Paltrow shares Tuscan breakfast recipe online, fans react - 12 mins ago

-

Over 30 More Countries Could Be Put on Travel Ban by US—Reports - 39 mins ago

-

Reds vs. Tigers Highlights | MLB on FOX - 48 mins ago

-

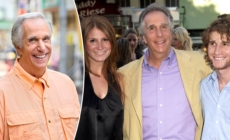

Henry Winkler shares parenting wisdom after Father’s Day surprise - 52 mins ago

-

2 killed and 32 injured after a bridge collapses at a tourist destination in western India - about 1 hour ago

-

Two Surprise Teams Linked to Kevin Durant in Trade Rumors - about 1 hour ago

-

Trey Hendrickson, Bengals reportedly in contract talks after minicamp holdout - 2 hours ago

-

Daniel Jones Praised for Strong First Impression With Colts - 2 hours ago

-

Big Noon Conversations with Marcus Freeman premieres June 16th | Official Trailer - 2 hours ago

How L.A. General finds names for its John Doe patients

He had a buzz cut and brown eyes, a stubbly beard and a wrestler’s build.

He did not have a wallet or phone; he could not state his name. He arrived at Los Angeles General Medical Center one cloudy day this winter just as thousands of people do every year: alone and unknown.

Some 130,000 people are brought each year to L.A. General’s emergency room. Many are unconscious, incapacitated or too unwell to tell staff who they are.

Nearly all these Jane and John Does are identified within 48 hours or so of admission. But every year, a few dozen elude social workers’ determined efforts to figure out who they are.

Too sick to be discharged yet lacking the identification they need to be transferred to a more appropriate facility, they stay at L.A.’s busiest trauma hospital for weeks. Sometimes months. Occasionally years.

That’s an outcome no one wants. And so hospital staff did for the buzz cut man what they do once every other possibility is exhausted.

Social workers cobbled together the tiny bit of information they could legally share: his height and weight, his estimated age, his date of admission, the place where he was found. They stood over his hospital bed and took his photograph.

Then they asked the 10 million people of Los Angeles County: Does anyone know who this is?

This unidentified patient arrived at L.A. General on Feb. 6 after being found unconscious in East Hollywood.

(Los Angeles General Medical Center)

-

Share via

Just before 8 a.m. on Feb. 16, paramedics responded to a medical emergency at 1037 N. Vermont Ave.

The man was face-down on a stretch of sidewalk lined with chain-link fences and sandbags, near a public restroom and the entrance to the Vermont/Santa Monica subway stop. Pink scrape marks blossomed above and below his right eye.

Paramedics estimated he was about 30 years old. Hospital staff guessed 35 to 40.

He had no possessions that might offer clues: no phone, no wallet, no tickets or receipts crumpled in his pockets.

He could not state his name or answer any questions. The hospital admitted him under a name the English-speaking world has used for centuries when a legal name can’t be verified: John Doe.

The vast majority of patients admitted as John Does leave as themselves. The unconscious wake up. The intoxicated sober up. Frantic relatives call the hospital looking for a missing loved one, or police arrive seeking their suspect.

None of these things happened for the man from North Vermont. When he finally opened his eyes, his language was minimal: a few indistinct words — possibly English, possibly Spanish — and nothing that sounded like a name.

Social workers wrote down everything they knew for sure about their patient: his height (4 feet, 10 inches), his weight (181 pounds), the color of his eyes (dark brown).

Then they started following the trail that typically leads to identification.

The ambulance crew didn’t recognize him, and the run sheet — the document paramedics use to record patients’ condition and care — had no revelatory details.

They checked Google Maps. Any nearby shelter whose manager they could call to ask about a missing resident? Nope. Was there an apartment building whose residents might recognize his photo? Nothing.

A second photo L.A. General released to the public in search of a name or next of kin for this unidentified patient found in East Hollywood.

(Los Angeles General Medical Center)

They clicked through county databases. His details didn’t align with any previously admitted hospital patient, or anyone in the mental health system. No missing-persons report matched his description; social workers couldn’t find a mention of someone like him in any social media posts.

An anonymous patient is an administrative problem. It’s also a safety concern. If a patient can’t state their name, they probably also can’t say if they have life-threatening allergies or are taking any medications, said Dr. Chase Coffey, who oversees the hospital’s social work team.

“We do our darndest to deliver safe, effective, high-quality care in these scenarios, but we run into limits there,” he said.

Federal law requires hospitals to guard patient privacy zealously, and L.A. General is no exception. But given that virtually every hospital deals with unnamed patients, California carves out an exception for unidentified people who can’t make their own healthcare decisions. In such instances, hospitals can go public with information that could locate their patient’s next of kin.

On March 3, nearly two weeks after the man’s arrival, a press release went live on the county’s website and pinged in the inboxes of reporters across the region.

“Los Angeles General Medical Center, a public hospital run by the L.A. County Department of Health Services, is seeking the media and public’s help in identifying a patient,” the flier said. In the photograph the man gazed up from his hospital bed, eyes fixed somewhere past the camera, looking as lost as could be.

The buzz cut man from North Vermont was not the only Doe in the hospital’s care.

On the same March 3 morning, the county asked for help identifying a wisp-thin elderly man with a grizzled beard and swollen black eye who’d been found in Monterey Park’s Edison Trails Park.

Three days later, it sent out a bulletin for a gray-haired Jane Doe picked up near Echo Park Lake. In her photo she was unconscious and intubated, a bruise forming on her forehead, wires curling around her.

L.A. General seeks identification for a female patient who arrived in late May.

(Los Angeles General Medical Center)

By the end of the month, L.A. General would ask the public to identify four more men and women found alone in parks and on streets across the county, people whose cognitive state or medical condition left them unable to speak for themselves.

All of the hospital’s Does are found in L.A. County. That doesn’t mean they live here.

L.A. General is 2 miles from Union Station, where buses and trains deposit people traveling from all over North America. A few years ago, Coffey and social work supervisor Jose Hernandez found themselves trying to place an elderly couple from Nevada, both suffering from cognitive decline, who arrived at the station and couldn’t recall who they were or where they meant to go.

Fingerprinting is rarely an option. The federal fingerprint database can be accessed only for patients who are dying or are the subject of a police investigation, hospital staff said.

Even if those criteria are met, the database will only yield a name if the person’s fingerprints are already in the system. And even that’s not always enough.

Late last year, law enforcement ran the prints of an unidentified female patient who had been involved in a police incident. The system returned a name — one the patient adamantly insisted was not hers.

“Now the question is, is she confused? Do we have the wrong fingerprints-to-name match? Is there a mismatch? Is there a person using a different identity?” said Coffey. “Now what do we do?”

In end-of-the-rope scenarios such as this, the hospital turns to the public.

The press releases are carefully phrased. The hospital can disclose just enough information to make the patient recognizable to those who know them, but not a word more. Federal laws forbid references to the patient’s mental health, substance use, developmental disability or HIV status.

The hospital is trying to find next of kin for a 26-year-old man admitted in March.

(Los Angeles General Medical Center)

The releases are posted on the county’s website and social media channels. Local media outlets often publicize them further.

In “the best outcome that we get, we send [the notice] out and we get a hit within a couple of days. We start getting calls from the community saying, ‘Oh, we know who this patient is,’” Hernandez said.

About 50% of releases lead to such positive outcomes. For the other half of patients, the chance of being named gets a little smaller with every day that the phone doesn’t ring.

“If we don’t know who you are after a month, that’s when it becomes decreasingly likely that we’re going to figure it out,” said Dr. Brad Spellberg, the hospital’s chief medical officer.

On April 9, nearly two months after the buzz cut man’s arrival at L.A. General, the hospital sent out a second release about him. His scrapes had healed. His black hair was longer. His stubble had grown into a wispy beard.

“Patient occasionally mentions that he lives on 41st Street and Walton Avenue,” the release said. “Primarily Spanish speaking.” But he still had no name.

It is possible for a person in this situation to be stuck at L.A. General for the rest of their lives.

One man hit by a car on Santa Monica Boulevard in January 2017 lived for nearly two years with a traumatic brain injury before dying unidentified in the hospital. As of late 2024, a few Does had been there for more than a year.

1. This woman, believed to be 55, was found outside Los Angeles General Medical Center. 2. This patient, who was found in Pasadena, has a tattoo of a small cross on his left forearm and small star tattoo on his left bicep. 3. This patient, believed to be about 50 years old, was found on East 5th Street in downtown Los Angeles. (Los Angeles General Medical Center)

If a patient has no identity, L.A. General can’t figure out who insures them. And in the U.S. healthcare system, not having a guarantee of payment is almost worse than not having a name.

Skilled nursing facilities, group homes and rehabilitation centers won’t take people who don’t have anyone to pay for them, Spellberg said. The county Public Guardian serves as a conservator for vulnerable disabled residents, but can’t accept nameless cases.

Unless a patient recovers sufficiently to check themselves out, they are stuck in a lose-lose scenario. They can’t be discharged from L.A. General, whose 600 beds are desperately needed by the county’s most critically ill and injured, but also can’t move on to a facility that provides the care they need.

“We’re the busiest trauma center west of Texas in the United States,” Spellberg said. “If our bed is taken up by someone who really doesn’t need to be in the [trauma] hospital but can’t leave … that’s a bed that’s not available for other patients who need it.”

L.A. General is staffed to handle crises, not long-term care of people with dementia or traumatic brain injuries.

Bedbound patients could get pressure sores if they aren’t turned frequently enough. Mobile patients could wander the hospital’s corridors, or fall and injure themselves.

“You’re trapping the patient in the wrong care environment,” Spellberg said. “They literally become a hostage in the hospital, for months to years.”

The man found in Edison Trails Park eventually left the hospital. So did the gray-haired woman, whose name was at last confirmed.

The man from North Vermont is still at L.A. General, his identity as much a mystery as the day he arrived four months ago.

The Does keep coming: An elderly man found near Seventh and Flower streets. A young man found near railroad tracks. A man with burn injuries and a graying beard; another unconscious and badly bruised.

All sick or injured, all separated from their names, all their futures riding on a single question: Does anyone know who this is?

If you have information about an individual pictured here, contact L.A. General’s Social Work Department from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday at (323) 409-5253. Outside of those hours, call the Department of Emergency Medicine’s Social Work Department at (323) 409-6883.

Source link