-

Trump says CEO of Intel must resign, calling him “highly conflicted” - 7 mins ago

-

Juan Soto Makes Telling Admission on Mets Offense as Struggles Continue - 13 mins ago

-

2025 FedEx St. Jude Championship tee times, pairing, featured groups for Thursday’s Round 1 - 31 mins ago

-

No charges for L.A. County deputy who shot man in back in 2021 - 34 mins ago

-

Map Shows Where US Will Start Deep Sea Mining in the Pacific - 55 mins ago

-

Drinking sugar may be worse for you than eating it, plus Dollywood tops Disney for best amusement park - 57 mins ago

-

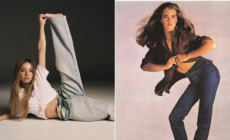

Sydney Sweeney jeans ad controversy echoes Brooke Shields Calvin Klein campaign - 59 mins ago

-

Buda Castle Comes Alive with Protestant Celebration This August 20 - about 1 hour ago

-

Millions of Californians may lose health coverage because of new Medicaid work requirements - about 1 hour ago

-

LA Galaxy vs Santos Laguna: Leagues Cup preview, odds, how to watch, time - about 1 hour ago

L.A. County unlikely to fight probation takeover — as long as receiver battles problem staffers

When a federal court appointed a receiver to take over a Mississippi jail plagued by inmate deaths three years ago, the Hinds County supervisors decried the move as “utterly unaccountable” to voters.

When a judge picked a manager for Rikers Island this summer after decades of disorder, New York City Mayor Eric Adams dismissed the decision as excessive oversight.

But there wasn’t much of that dissent after Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta’s announcement two weeks ago that he planned to ask a judge to appoint a receiver to run L.A. County’s beleaguered juvenile halls.

“I’m looking at it as help — much needed help,” said Supervisor Janice Hahn, whose district includes Los Padrinos Juvenile Hall in Downey, which has been the site of a riot, escape attempts and multiple overdoses since it reopened in 2023. “I think it’s important that the county not fight it.”

Given the history of crises at the juvenile halls, the county can’t mount much of an opposition, she noted.

“We don’t have a leg to stand on,” she said.

For years, the county’s juvenile halls have careened from one scandal to the next — a fatal overdose of a teen, an alleged guard-incited “fight club,” an unabating staffing crisis. In 2021, the county entered a court settlement with Bonta’s office, pledging to improve conditions inside the halls, now home to about 430 incarcerated youths ages 13 to 24.

Last month, Bonta said the county’s “repeated, constant and chronic” failure to adhere to the settlement left him with no choice but to ask the court to approve a receiver for the county’s two remaining halls. That official would, in effect, supplant the supervisors as the top decision-maker for the facilities, setting budgets and hiring staffers. The county, he emphasized, will still foot the bill for everything — a request that could prove financially risky for the cash-strapped county.

It’s an embarrassing rebuke of the county’s politicians; L.A. County would become the second county in the U.S. to lose control of its juvenile facilities to a receiver. Yet a majority of the board appears uninterested in fighting it — on one condition.

They want the receiver to go after the union contracts and civil service protections they say keep problem employees on the payroll.

“It is near impossible for them to be disciplined — let alone removed from their positions” said Supervisor Lindsey Horvath, whose district includes Barry J. Nidorf Juvenile Hall in Sylmar. “I don’t believe a receivership approach will be successful without changes to the staff and the employment agreement that governs how these halls operate.”

Los Padrinos Juvenile Hall in Downey has been the site of a riot, escape attempts and multiple overdoses since it reopened in 2023.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

On July 29, the three unions representing probation employees sent a letter to Horvath accusing her of “reckless, union-busting rhetoric” and ignoring state law that protects members’ collective bargaining rights.

“Let us be unequivocal: our union contracts and civil service protections do not shield wrongdoing. They uphold due process and ensure fair and lawful treatment of public servants,” the three union presidents wrote in the letter. “If the Court appoints the Receiver, we will hold him accountable to state law and to the terms of our contract.”

Absent some sweeping new power, Probation Chief Guillermo Viera Rosa warns, the receiver will run into the same obstacles as every other chief.

“Simply having a receiver saying do X, Y and Z isn’t going to change anything unless they have explicit powers that I haven’t had or that the county hasn’t been able to implement because of, for example, the civil service or unions,” Viera Rosa said. “If it’s simply additional oversight and putting another person to simply have a separate budget, but no new ideas or powers, then it’s a critical mistake.”

And potentially a costly one. County Chief Executive Fesia Davenport warned her bosses at a meeting last week that handing financial control to a receiver could have “significant impacts” to the county’s finances, which already have been wrecked with federal cuts, a $4-billion sex abuse settlement and costly labor negotiations.

Supervisor Kathryn Barger said she believes it’s still worth a shot.

“For decades, the Department has been hamstrung by entrenched staffing problems and organizational culture resistant to reform and accountability,” she said in a statement. “If a receiver can cut through the red tape that has stalled past reform efforts, then it’s a step worth taking.”

Soon after taking the job in 2023, Viera Rosa diagnosed his ailing department with a “call out culture.” Employees scheduled to work often didn’t show up for their shifts.

The problem, some staffers say, stems from violence in the halls, which makes many not want to come in. There are fights among the youths, which staffers are supposed to break up, as well as aggression directed at the staff. Thanks to a generous county leave policy, staffers have a large reserve of sick days, which they can use to miss a shift.

But fewer staffers make the conditions inside the halls more unstable. Those officers who do come in are sometimes required to stay for a double shift to address last-minute staffing problems, draining them and ruining their plans for the day. The lack of staff plunges the halls deeper into chaos, with no one to escort youths to their daily activities: school, exercise, medical appointments.

The probation department’s staffing problem dates back more than a decade, said former L.A. County Probation Chief Jerry Powers, who used send sheriff’s deputies to staffers’ homes to urge them to return to work.

“They’ve tried everything else. They’ve literally done everything that could possibly be done from a departmental perspective,” said Powers, who oversaw the agency from 2011 to 2015. “You’re going to have to give the receiver the authority to suspend contracts — whether it’s employment contracts, union contracts, broad authority to suspend civil service rules — just a tremendous amount of authority to really move the needle on this.”

That’s what happened in Cook County, the only juvenile detention facility in America to go into a receivership. Earl Dunlap, who served as the receiver, said the facility suffered from some of the same issues as L.A. County: notably, staffers who did not show up to work. A federal judge gave him the ability to get rid of a third of the staff.

“The place was a hellhole,” Dunlap said. “What you ended up with was a whole new culture.”

Viera Rosa said he sees no signs that the attorney general’s office is looking to go that big.

“I think it’s premature, given we have no indication from the court as to how they would create a receivership,” he said.

Lorenzo Arnold, a deputy probation officer, attends a rally held by the Coalition of Probation Unions in 2022. Probation unions have repeatedly demanded that the county do more to protect officers inside juvenile halls.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

Bonta’s office said in a statement the receiver will have the power to hire and fire staffers and “all other necessary decisions for compliance.”

“If the receivership is approved, the receiver would have the power to negotiate or renegotiate contracts and to petition the court to waive a contractual obligation in certain circumstances,” the his office said in a statement.

Michael Dempsey, who Bonta has asked to be appointed as receiver, said he couldn’t comment, citing confidentiality agreements. Dempsey, the head of the Council of Juvenile Justice Administrators, has served as the monitor over the halls during the settlement.

Legal experts say the question of whether a receiver appointed by a Superior Court judge could take on collective bargaining agreements is a murky one. Jonathan Byrd, a vice president with the deputy probation officers union, said the state should expect a wall of opposition if it tries to make changes to the contract.

“We will fight that,” he said, adding that he believed the contracts would be protected by decades of court precedent.

But he said he sees no sign that the attorney general’s office will use the receivership to chip away at union protections. Rather, the union is hopeful that Bonta will take a sledgehammer to the grip the supervisors have on the agency.

“We are cautiously optimistic, because we have not been able to get the support we need,” said Byrd, who said he wants the receiver to infuse the department with hundreds of new staff members.

Since 1979, receivers have taken over jails, prisons and juvenile halls just 14 times, according to Hernandez D. Stroud, a senior fellow with NYU School of Law’s Brennan Center for Justice, who tracks receiverships. Only four are active, he said, including two in California overseeing psychiatric and medical care within the state prison system. Recieverships typically last a few years, though the California medical care case has stretched for two decades.

Experts say overriding the union contract would be a rare — and politically fraught — power for a state judge to grant a receiver.

“Even in a federal receivership, they’ve sort of left the contracts alone,” said Don Specter, a senior staff attorney with the Prison Law Office, whose Supreme Court case focused on inadequate medical care for California prisoners led to a receiver. “That would be a last resort, usually.”

Source link