-

Ship attacked in the Red Sea after a bulk carrier sinking claimed by Yemen’s Houthi rebels - 8 mins ago

-

L.A.’s top prosecutor restores ‘normalcy.’ Can it last under Trump? - 10 mins ago

-

US Spy Plane Restarts Snooping on Russia as Trump Loses Patience With Putin - 29 mins ago

-

Who Are The 10 Best MLB Players 25 And Under Right Now? - 35 mins ago

-

High-Speed Internet to Reach the Furthest Corners of the Country - 49 mins ago

-

Baby dies after SoCal mom leaves him in hot car to get lip filler, police say - 52 mins ago

-

Russia launches another record drone attack, Ukrainian officials say - 57 mins ago

-

Tigers Reportedly Inquire About Former Gold Glove Third Baseman As Interest Grows - about 1 hour ago

-

Yankees Move All-Star Infielder Jazz Chisholm Jr. From Third Base Back to Second - about 1 hour ago

-

Explore Budapest’s Craft Beer Scene with a Beer Passport - about 1 hour ago

L.A. firestorms and Texas floods show communities are ill-prepared for worsening climate disasters

Two major climate disasters of 2025 — the Texas flooding that killed more than 100 people and the L.A. wildfires in January that resulted in 30 deaths and wiped out more than 15,000 homes and businesses — highlight the struggles officials face in fully preparing for extreme weather conditions.

In both cases, the National Weather Service offered clear warnings of potentially life-threatening weather events; in Los Angeles, warnings were given days before extraordinary winds — of up to 100 mph — slammed a region already suffering from a record-dry fall. Even in Texas, more than a day before catastrophic flooding hit Kerr County, state officials — on July 2 — reiterated the weather service’s warnings that “heavy rainfall with the potential to cause flash flooding is anticipated across West Texas and the Hill Country” through the Fourth of July weekend.

But for a variety of reasons, those warnings did not filter down with maximum urgency to various local agencies.

In Los Angeles, despite NWS warnings of “life-threatening, destructive” winds, Los Angeles officials decided not to pre-deploy hundreds of firefighters in advance of devastating wildfires, a Times investigation found. Mayor Karen Bass was overseas in Ghana when the devastating Palisades wildfire — which resulted in 12 deaths — spread rapidly on Jan. 7. The National Weather Service began conducting briefings on the expected fire risk as early as Dec. 30.

Even as a separate wildfire was underway in another part of L.A. County, officials responsible for Altadena failed to issue emergency evacuation orders in the western part of the unincorporated area until homes there were already on fire, according to a Times review of records, radio logs and interviews. Of the 18 people who died in the Eaton fire, 17 were in western Altadena.

Since then, there have been calls for sweeping reforms of how Los Angeles County prepares for disasters, and investigations into what went wrong.

California has endured a series of deadly fires, floods and landslides — some of which may have been exacerbated by climate change, as well as increased development in fire-prone areas — forcing state officials to improve evacuation planning. During landslides that ravaged Santa Barbara County and fires that burned though wine country and Paradise, residents complained about not getting alerts to impending danger. State and local officials said they have made improvements, but continued evacuation problems during the Palisades and Eaton fires in Southern California earlier this year show serious gaps still exist.

Some of the same soul-searching is going on in the wake of the Texas tragedy.

The massive, rapid rise in floodwaters in the middle of the night in Texas on the Fourth of July should spur officials to change how they think about warning people when extreme weather is forecast, experts say.

Besides the warning Texas issued on July 2, weather forecasters reiterated a warning of the chance of disaster along the Guadalupe River as much as 14 hours before floodwaters surged around Kerrville in Texas’ Kerr County — especially among nearby riverside campgrounds that have long been defined as having high flood risk, according to FEMA flood maps.

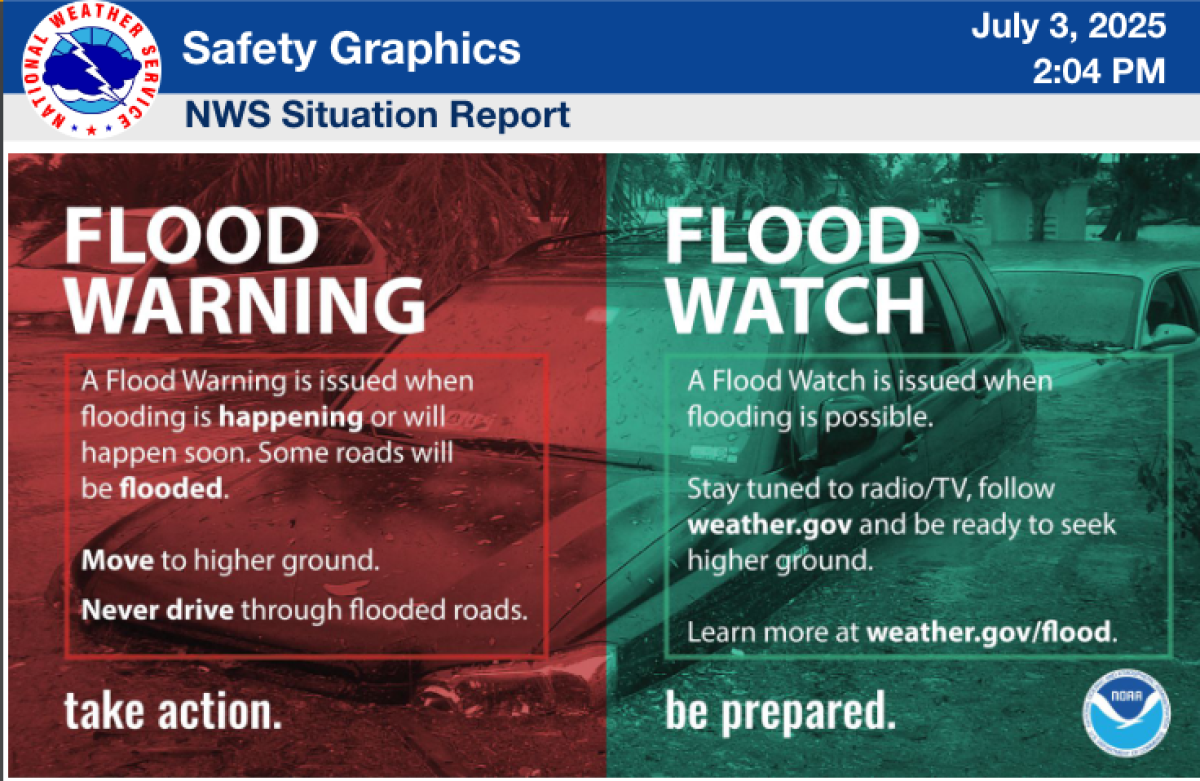

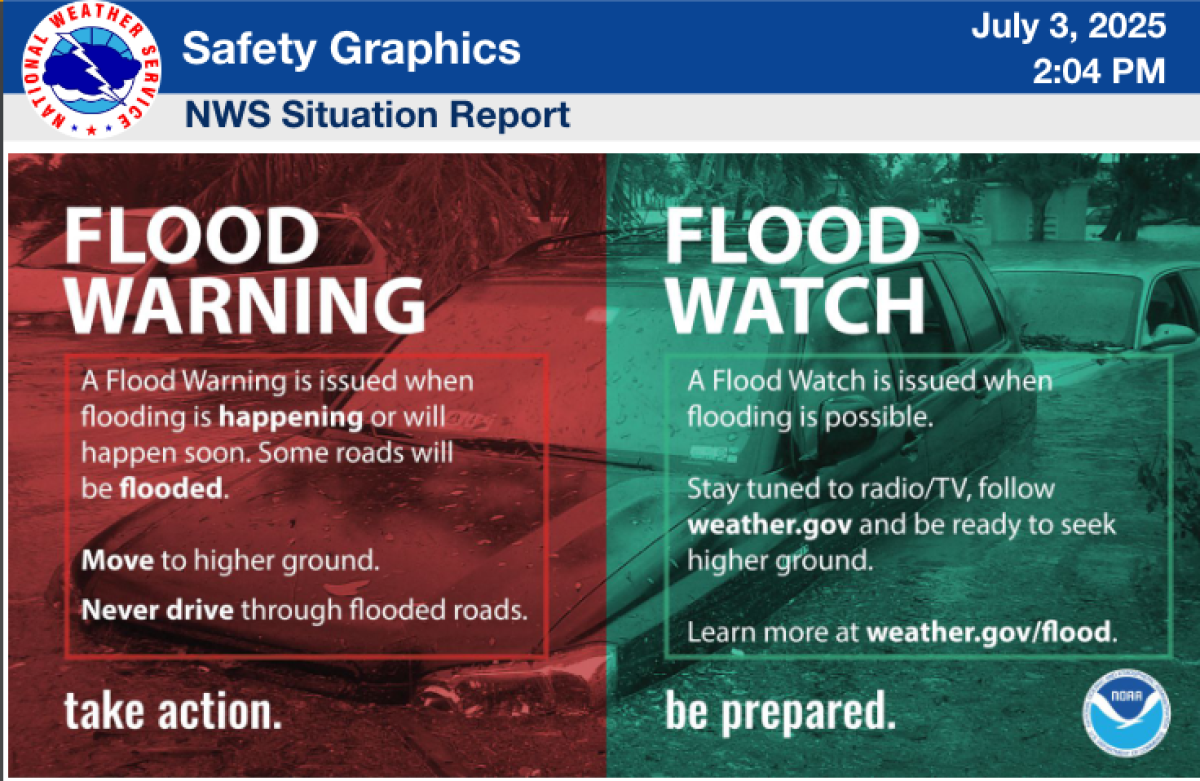

A National Weather Service briefing document, intended for local officials and news reporters, issued Thursday afternoon, warned of a flood watch for Kerr County, Texas. A devastating flood hit the area between 3:45 a.m. and 4:45 a.m. Friday.

(National Weather Service Austin/San Antonio office)

Yet the response of local officials indicated that some did not fully grasp the danger from floodwaters, with Rob Kelly, the top elected official of Kerr County, telling reporters that “rest assured, no one knew this kind of flood was coming.”

A Washington Post review of wireless emergency data found that Kerr County did not issue its own first Amber Alert-style warning to phones until two days after the deadliest day of flooding.

Those responses illustrate a flawed understanding of available warnings and past historical data out there that suggested a risk was there — especially for campers who were located right alongside a river prone to flash flooding.

Not only did the floodwaters hit a wide swath of Texas known as “Flash Flood Alley,” the Guadalupe River has been the site of tragedy before — 10 teenagers died in July 1987 as floodwaters surged near a campground. Despite warnings from law enforcement officials to not move vehicles through floodwaters, the camp decided to evacuate campers through a flooded area, and the last bus and van of the camp’s caravan became stuck in floodwaters. Four adults and 39 teenagers were swept away, including the 10 who drowned, according to the weather service.

And the Guadalupe River was among four rivers in Texas hit hard by historic flooding in December of 1991 and January of 1992. Thirteen died.

On Thursday, the National Weather Service office for Austin/San Antonio had issued a flood watch — indicating that flooding may be possible — for Kerr County at 1:18 p.m. That was more than 14 hours before floodwaters surged into Kerrville, which began somewhere between 3:45 a.m. and 4:45 a.m. on Friday, according to flood gauge data on the river.

“Locally heavy rainfall could cause flash flooding across portions of South Central Texas,” the weather service said Thursday afternoon, requesting an immediate broadcast of the urgent flood watch. “Excessive runoff may result in flooding of rivers.”

And with the dangers on the minds of some after a flash flood in June in nearby San Antonio killed 13 people, local media reiterated state warnings about the potential for flooding.

“It does not take a lot of water to create a hazard,” a spokesperson for the Texas Division of Emergency Management said on a TV broadcast that aired on Thursday. “Really, it’s so important to just be weather aware.”

A slide from the National Weather Service briefing document to local officials Thursday afternoon defines a flood watch as stating “flooding is possible.”

(National Weather Service Austin/San Antonio office)

Yet news accounts indicate that local officials, even as little as less than hour ahead of devastating flooding, were unaware of the risk. The Associated Press quoted the Kerrville city manager, Dalton Rice, as saying he was jogging along the river early in the morning and didn’t notice any problems at 4 a.m.

That was more than two hours after the National Weather Service office for Austin/San Antonio issued at 1:14 a.m. a flash-flood warning for central Kerr County, warning that radar was indicating thunderstorms were producing heavy rain and warned of “life threatening flash flooding.” The weather service requested an activation of the Emergency Alert System.

News accounts indicated that campers at Camp Mystic — where 27 campers and counselors were killed by floodwaters — were caught by such surprise that the girls needing rescue, some as young as 7 and 8, were found in their pajamas.

“I wish something like this would result in more proactive closures,” said Alex Tardy, who recently retired as the warning coordination meteorologist for the National Weather Service office in San Diego. “The only way to prevent people from dying or getting injured is you’d have to close the area. You’d have to evacuate,” he said, and do it before the rain began.

Tardy said he understands sending kids home just before the Fourth of July would have been a tough call to make. “Telling hundreds of kids, ‘Sorry, it’s Fourth of July. The event’s canceled. You need to go home,’ it’s not easy to do,” Tardy said. “It typically doesn’t happen because, most of the time … even if heavy rains is expected, most of the time, it doesn’t result in anything major.”

But parents and camp organizers and officials should note that many camps are set up in flood-prone parts of rivers, “because that’s where it’s beautiful, that’s where it’s lush,” Tardy said.

If camp owners are not going to move these campsites, then camp organizers and local officials need to consider how difficult it would be to evacuate a camp with hundreds of kids if a warning was sounded just after 1 a.m., given the hours and days of earlier forecasts warning of the possibility of flooding. The area where the flooding hit is particularly dangerous for flash flooding, with rain falling over hills, meaning floodwaters will move fast.

“All these campsites are built in valleys and in river drainages. They’re built at the low spot,” Tardy said. “We always tell people, ‘If you’re going hiking, if you expect any thunderstorm, you better have a plan B, or you might want to cancel your trip, because you’re going to be screwed” if flooding hits — and camp organizers and officials should be ready to have such a plan in place.

A key question is what the response was of local officials to the weather service’s warnings.

“Did they just blow it off and say, ‘We always have flood watches’?” Tardy said.

“If I was an emergency manager and it was Southern California, and the monsoon was kind of building over the San Gabriels or up by Big Bear, if I had a flood watch, and I had people up along the Santa Ana River or something like that, yes,” — that would be an indication to pack up the campers and send them home, Tardy said.

That may be an easier call to make given that Southern California is mostly sunny in the summer, and a harder decision along Texas’ Guadalupe River, where thunderstorms are more common. But, Tardy said, perhaps local officials, in consulting with the local weather service office, could refine a threshold for which kind of conditions might prompt a closure of campgrounds right along a riverside’s edge.

People at other campgrounds have also died from floodwaters. In 2010, there were 20 deaths after the Little Missouri River flooded and inundated most of Arkansas’ Albert Pike Recreation Area, the weather service said.

At a news conference, Rice, the Kerrville city manager, said the decision to call an evacuation is “a delicate balance, because if you evacuate too late, you then risk putting buses, or cars, or vehicles, or campers on roads into low-water areas trying to get them out, which then can make it even more challenging. Because these flash floods happen very quickly.” He added: “It’s very tough to make those calls. Because what we also don’t want to do is cry wolf.”

Others note it’s the job of these public officials to make these calls.

“It’s every parent’s nightmare,” Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) said at a news conference Monday. “If we could go back and do it again, we would evacuate particularly those in the most vulnerable areas — the young children in the cabins close to the water — we would remove them and get them to higher ground.”

With climate change bringing more extreme deadly weather, local emergency management officials around the nation are trying to keep up.

In 2023, officials in Hawaii were caught off guard despite a history of dangerous wind storms on Maui that put parts of the island at high wildfire risk, and advance warnings from the National Weather Service about the risk of high fire weather danger.

According to an after-action report, the weather service told firefighters on Aug. 3 of “critical fire weather conditions,” and Maui emergency managers spoke on Aug. 6 of a “serious fire and damaging wind threat.”

Yet, Maui’s top emergency management official was not on the island on Aug. 8, the day the deadliest U.S. wildfire in a century began, killing 102 people and leveling a swath of the town that once hosted the royal residence of the Hawaiian king.

Santa Barbara County remains haunted by questions of what could’ve been done better ahead of vicious landslides that killed 23 people in Montecito in 2018, a situation plagued by inconsistent evacuation information and a failure to send out Amber Alert-style bulletins to cellphones until after the mud started flowing.

Source link