-

Timothy Busfield enters plea on child sex abuse charges - 48 mins ago

-

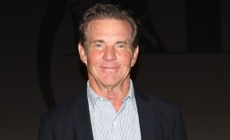

Dennis Quaid describes his political stance as common-sense independent - 2 hours ago

-

Phillies Lose 5-Year Veteran Free Agent to Diamondbacks - 2 hours ago

-

Estelle Getty ‘Golden Girls’ star former home for sale for $7.65M - 2 hours ago

-

Former worship leader and ‘American Idol’ hopeful charged with murder in wife’s shooting death - 2 hours ago

-

From the rubble, the show must go on for one of Gaza’s surviving radio stations - 2 hours ago

-

Seahawks Star Jaxon Smith-Njigba: ‘I Deserve to be Highest-Paid Wide Receiver’ - 2 hours ago

-

The company Ridwell tries to recycle the really difficult plastics - 3 hours ago

-

‘Filthy Fortunes’ star finds over $1 million in hidden money in American homes - 3 hours ago

-

One of Gaza’s surviving radio stations returns to the airwaves - 3 hours ago

The company Ridwell tries to recycle the really difficult plastics

SAN LEANDRO — A start-up recycling company has a message for its potential, environmentally conscious customers: Don’t send your problem garbage to the landfill; put it on your front porch.

The company is Ridwell, and if you drive the residential streets of the San Francisco Bay Area or Los Angeles, you’re likely to see the company’s signature white metal boxes on porches.

The boxes are for empty tortilla chip and plastic produce bags, used clothing, light bulbs and batteries. In some locations, polystyrene peanuts. All the things you’re not supposed to put in the blue recycle bin, but wish you could.

The Seattle-based waste service is geared toward people who worry their waste will end up in the landfill, or get exported to a developing country in Asia. They sort their waste into colorfully labeled canvas bags the company provides, and wait for a Ridwell pickup.

“Sorting is our special sauce,” said Gerrine Pan, the company’s vice president of partnerships. Part of the reason the company is successful at finding markets — or buyers — for its waste, she said, is that it’s sorted and pretty clean (unlike the food-contaminated jumble of waste that gets stuffed in many blue bins).

The company promises to distribute all that waste to specialty recyclers, manufacturers, even thrift shops.

Bagged recyclables sit in boxes at the Ridwell warehouse in San Leandro.

But critics say the boutique waste hauler is not accomplishing anything environmentally useful and is selling the public a myth: that these plastics — multilayer plastic film, plastic bags, polystyrene — can be taken care of responsibly. The service would be benign, they say, if it stuck to the delivery of materials, such as light bulbs and batteries, that can be recycled.

Most local waste haulers don’t accept batteries and light bulbs because they can pose a hazard to workers and equipment.

The base Ridwell membership is $20 a month. For that, a driver will come by every two weeks and take the presorted bags to a warehouse where they’re emptied, the contents stacked and collected, until there’s enough to deliver to a facility that will take it.

Sorted recyclable items await transport at the Ridwell central warehouse.

Company lore is that founder Ryan Metzger and his son were frustrated that so many things weren’t accepted by their local hauler for recycling. The two sat down and researched where to take the stuff, then decided to scale up and serve their neighbors.

The company has since expanded to Vancouver, Wash.; Portland, Ore.; San Francisco; Los Angeles; Denver; Austin, Texas; Minneapolis and Atlanta. It now boasts more than 130,000 customers nationwide.

Most of the waste is delivered locally. But some of it travels hundreds, if not thousands of miles.

For instance, multilayer plastic bags — those that hold snack chips, candy and coffee beans — are the scourge of municipal garbage haulers because they cannot be recycled, and if put in the blue bins, can damage mechanical sorting machines. Ridwell, however, found Hydroblox, a company that melts the multilayer films into hard, plastic bricks that can be used for drainage projects in landscaping and road construction.

But this arrangement highlights some of the limitations of the nascent industry. Hydroblox owner Ed Greiser said he can take only so many chip bags. The company is growing, but it’s still pretty small, and he’s typically maxed out on the bags.

Ridwell workers sift through recyclables.

“This article is going to be a nightmare for me,” he told a Times reporter, because it’s likely to attract a parade of unsolicited garbage trucks looking to dump their bags. “I’m not the solution.”

In addition, Greiser’s two facilities are in Pennsylvania, more than 2,700 miles from most West Coast pickup points, a steep transportation cost for a plastic bag that could instead go 20 miles to a local landfill.

Ridwell also has recently expanded to serve customers outside its pickup cities. It sends special plastic bags to these far-flung subscribers so they can sort their waste and ship it back.

Again, critics say the company’s decision to operate a service that is dependent on plastic bags and requires extensive transport undermines their environmental bona fides. And they worry that a narrative suggesting all waste can be dealt with responsibly is false and misleading. That misconception, they say, contributes to the glut of plastic piling up in our rivers and oceans, and inside our bodies.

“There is typically a reason why a given product isn’t being recycled through curbside collection, and it usually isn’t for lack of effort by cities and counties,” said Nick Lapis, director of advocacy for Californians Against Waste. “Most of the material being collected by boutique collection services like Ridwell are either very difficult to manage or lack strong recycling markets.”

Manufacturers of plastic packaging, not consumers, should pay for recycling products and packaging at the end of their life, he said. For regular people, “having to pay an extra fee to handle the unrecyclable plastic packaging that is thrust upon us every day is antithetical to every concept of producer responsibility.”

Earlier this month, the anti-plastic group Beyond Plastics published a disparaging report on boutique waste haulers, including Ridwell, accusing them of providing cover for plastic and packaging manufacturers who want people to believe their waste is being recycled.

A Ridwell employee inserts a bag of recyclables into a bailer at the San Leandro warehouse.

Ridwell offered a visitor a tour of its Bay Area warehouse in San Leandro. The spacious facility behind a Home Depot and Walmart was crowded with steel drums filled with alternating layers of batteries and fire-retardant pellets, boxes of light bulbs and piles of used clothes, all destined for recyclers, upcyclers and thrift stores.

While the public may think of recycling as a largely physical process, it’s actually a market: a function of how well a material can be profitably turned into something else.

Boxes of clothing await transport.

Metzger, Ridwell’s chief executive, said some of the material his company collects can be sold. Some of it is given away, “and some we pay to have responsibly processed.” The more technically challenging the plastic, the more likely Ridwell will have to pay to deal with it, he said.

He said the company vets all the places it sends its waste, giving preference to those that use items a second time over those that melt them down or shred them to make them into something else. It also gives preference to partners that are local.

He said his company is “careful not to present plastic recycling as a cure-all,” and it turns away some materials, for example vinyl shower curtains, “because we don’t have a downstream partner we can stand behind.”

And while Metzger agrees with many of Beyond Plastic’s concerns, he has observed that “when customers actively sort and see which items require special handling, it often increases their awareness of where plastic waste is coming from in their own lives … [leading] them to change purchasing habits and avoid certain packaging altogether.”

Source link