-

Culture Minister welcomes high number of university entrants - 10 mins ago

-

Rays vs. Reds Highlights | MLB on FOX - 38 mins ago

-

Unemployment rate at 4.3 percent - 44 mins ago

-

Lottie Woad Sends Powerful Five-Word Message Ahead Of Women’s Open - 48 mins ago

-

Alex Palou recaps 8th win of season after first place finish at Laguna Seca | VICTORY LAP - about 1 hour ago

-

Orbán: Here are the 5 pillars of our strategy to stay out of wars to come - about 1 hour ago

-

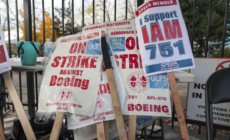

Thousands of Boeing Employees Could Strike Next Week: What To Know? - about 1 hour ago

-

TBT 2025 Quarterfinals Recap: Aftershocks, We Are D3 Advance - 2 hours ago

-

Man Dies as Family Dollar Store Roof Collapses in Missouri - 2 hours ago

-

Black Sabbath bassist remembers ‘frail’ Ozzy in emotional final performance - 3 hours ago

Trump threatened Vietnam with a huge tariff. How’s that going over in Little Saigon?

ABC Supermarket in the heart of Little Saigon is like a Donald Trump tariff rant come to fragrant, tasty life.

Sorghum liquors from China. Frozen seafood from Malaysia. Thai fish sauce. Japanese candies. A galaxy of products from Vietnam, of course.

All of these imports would be slammed by the massive tariffs that Trump threatened to impose on many Asian nations until putting a pause on the plan, with Vietnam, at 46%, among the highest.

But in Little Saigon, enmity for the Vietnamese government, which proclaims itself Communist even as the country’s economy developed a niche exporting manufactured goods, thrives among the older generation, many of whom arrived in the U.S. as refugees after the fall of Saigon nearly 50 years ago.

Some are even willing to pay higher prices if it means the Communist regime will suffer.

“Everything will become more expensive, but if it hurts the Vietnamese government, I’m for it,” said Diep Truong, 65, whose cart held a jackfruit the size of a pillow. “If the president says it will help America, then I’m for it.”

But John Nguyen, 39, worries that consumers accustomed to a wide variety of imported foods from Asia won’t be able to afford the higher prices that tariffs could bring.

“All these people aren’t rich,” said Nguyen, the son of Vietnamese refugees, as he gestured to other shoppers in the parking lot of the supermarket in Westminster, his cart groaning with bags of rice and canned pho. “So much of Vietnamese food comes from Vietnam. How are we supposed to be able to pay more money for food when it’s already expensive?”

The tech worker didn’t vote in the 2024 election, despising Trump but unimpressed with Kamala Harris. His parents are Trump supporters and don’t seem to mind the president’s trade war.

“Let’s see how they feel when we’re paying way more for our dinner,” he said bitterly.

Shoppers at the Little Saigon market Sieu Thi ABC Supermarket will invariably find higher prices after the Trump administration’s tariffs kick in on Vietnam.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

That generational divide was evident in many of the conversations I had with shoppers and business owners in Little Saigon, where the Republican Party has long held sway for its traditional anti-Communist stance and where support for Trump remains strong among older Vietnamese immigrants, even as many of their children reject the GOP.

Over the decades, doing business with Vietnam has evolved from an affront that could result in death threats to a common profession that keeps Little Saigon stores stocked with affordable goods.

Stephanie Nguyen fled Vietnam 30 years ago and now runs a business that imports supplements and skin care products from Japan, which also faced a steep tariff. She admitted that the stock market instability caused by Trump’s tariff threats has walloped her portfolio.

“But we have to sacrifice a bit for the benefit of this country,” said the 52-year-old, who “proudly” voted for Trump three times. “I can’t go back to Vietnam. This is my home country now, so we need to do what we have to do to protect and support the USA.”

Other importers fear for their bottom line, including some in the nail salon industry that has lifted many Vietnamese Americans into the middle class.

Vy Nguyen moved to the U.S. nine years ago for college and now runs import operations for Nghia, her family’s nail-trimming equipment business.

The tariffs “would be devastating if it happens,” she said at Nghia’s small showroom in Garden Grove. “I understand where he [Trump] is coming from, but all of this falls on small business and customers.”

Vy Nguyen, who runs U.S. operations for Nghia, a Vietnam company owned by her family that makes and sells high-end manicure tools for nail salons, talks to a customer who is buying products in her store in Garden Grove. She said the Trump administration’s tariffs are causing prices to rise on everything. “It’s devastating for the end user. Vietnamese technicians buy their own tools,” Nguyen said.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Nguyen, 26, had just returned from a trade show where the president’s trade war “was all that people wanted to talk about.”

She already had to slash a recent order from Vietnam from $1 million to $500,000 due to a lower sales forecast if the tariffs are implemented. The shipment will take far longer to arrive than usual and cost more, because “everyone is trying to export right now” to stay within Trump’s 90-day tariff pause.

“I know that in the American community, one or two dollars more doesn’t seem much,” Nguyen said. “But for Vietnamese, even that increase is super sensitive to everyone.”

Nearby at Tu Luc Bookstore, manager Eric Duong estimated that 70% of the Vietnamese-language books on the shelves are imported from Vietnam.

Duong didn’t want to offer an opinion on “something that hasn’t happened yet.” But he said that Tu Luc, a destination for readers for 41 years, has already seen a big drop in sales this year.

If tariffs do come, “we would try to do the best and keep it affordable, but we don’t know what’s next,” Duong said. “We’re just waiting for Trump to do something, and that waiting is hard.”

People congregate inside the Asian Garden Mall in Westminster.

(Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

Vietnam is the world’s sixth-largest exporter to the U.S., from major companies like Nike and Lululemon to the small makers in stock at ABC Supermarket. The U.S. trade deficit with Vietnam is about $123.5 billion, putting the country near the top of Trump’s list for “reciprocal” tariffs.

This would have been unimaginable a generation ago.

When then-President Bill Clinton announced the end of a U.S. trade embargo against Vietnam in 1994, hundreds of people rallied on Bolsa Avenue, Little Saigon’s main drag, to decry the decision.

For a good decade afterward, anyone in Little Saigon who openly sought to establish business relations with Vietnam could expect accusations of being a Communist. Protesters greeted Vietnamese government officials who came to Orange County to talk opportunities.

One of those protesters was Janet Nguyen. As an O.C. supervisor in 2007, she stood outside a Dana Point resort with hundreds of others to blast an appearance by Vietnam’s then-president, Nguyen Minh Triet.

Janet Nguyen in Newport Beach in 2022.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Nguyen, who served as a state Assembly member and senator before returning to the O.C. Board of Supervisors last year, has sent a letter to every American president since George W. Bush, urging them not to be easy on Vietnam when it comes to free trade.

“In Vietnam, the government gets wealthier, not the people,” said the supervisor, 48, who fled Vietnam on a boat with her family as a child. “If you’re going to benefit from America, you’ve got to benefit your people, not the Communist Party.”

She admitted that Trump’s strategy — including tariffs on countries other than Vietnam — could affect her district, which encompasses Little Saigon.

“It might spike prices, and services might be reduced, and projects will have to be put on pause,” Nguyen said. “But we’re just going to have to wait and see.”

Vietnamese American Chamber of Commerce Chair Tim Nguyen, 42, said his group has received a “spike” of website visits and phone calls from frantic members.

“Everyone is very on the edge trying to see what to do,” said Nguyen, who imported pickup truck parts from China until Trump’s 2019 tariffs helped sink his company. “The best thing we can do right now is be a conveyor of information so we can calm people down.”

The chamber, more than any other group in Little Saigon, has been at the forefront of promoting trade with Vietnam, often at great personal cost. Its founding president, Dr. Co Pham, wore a bulletproof vest at his medical practice because of threats stemming from his stance that better business relations could bring freedom to his homeland.

When Tam Nguyen was asked to succeed Pham in 2009, he worried that doing so “might expose my family’s business to criticism.”

A buddha statue and other items inside the Asian Garden Mall.

(Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

Nguyen, 51, whose family fled Vietnam when he was a baby, is the chair of Advance Beauty College, a beauty school started by his parents that has trained tens of thousands of manicurists over the decades.

Growing up, Nguyen felt a gap with the older generation, who “were so adamant to not do any trade with Vietnam. I could never understand their trauma.”

Now, he said, “a Little Saigon business is a global business,” and “everyone seems to be importing something.”

Over the years, the tags on his clothing have progressed through a parade of Asian countries: China, Japan, Indonesia.

“Today, it’s ‘Made in Vietnam,’ and it brings me great pride,” Nguyen said. “My cousins back in Vietnam have better jobs now. I don’t have the angst of my parents’ generation. And it’s so normalized to the point where my children don’t even think of [Vietnamese products] as being political.”

He is concerned that the tariffs will have a ripple effect across Little Saigon, because “we’re not just the workforce — we’re the entire supply chain. But if anything, this will bring us together, and we’ll figure it all out. Our people are resilient — we adapt. That’s what we’ve done for 50 years, and look what we have created.”

Customers at the Coffee Factory in Westminster.

(Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

At Coffee Factory in Westminster last year, Clinton campaigned for Derek Tran, who later won his congressional race.

A generation ago, community members would have shouted down Clinton for normalizing relations with Vietnam. This time around, it was all people with smartphones joyously taking photos.

I stopped by the cafe on a recent morning with my colleague Anh Do, who introduced me to customers and sometimes helped translate. Some people told us they took Trump’s side on the tariffs — and they didn’t have anything nice to say about the Vietnamese government.

A cup of tea rests on top of a Vietnamese newspaper at Coffee Factory.

(Carlin Stiehl/For The Times)

Thanh Trieu, 55, whose family is in the pharmacy business, sat outside with a group of friends. Resting on the table next to a pack of cigarettes, a copy of the Vietnamese-language newspaper Vien Dong included a column about the tariffs, complete with a photo of Trump.

“It’s not gonna affect us immediately,” Trieu said. “America has so much debt. We have no choice but to do this. Someone’s gonna get hurt, someone’s gonna get profit. It might as well be us [Americans] who win.”

Giau Nguyen, 63, walked over from his hair salon a few doors down, decked out in an Elvis-style pompadour and a shirt featuring the U.S. Constitution underneath a pattern of bald eagles and the Stars and Stripes.

He acknowledged that tariffs would hurt his business, “but just a little, not much. This is going to hurt in the short run, but at the end it’s fair, and I support what’s fair. Other countries have been cheating America in the long run.”

Inside, Tony Fukukawa was about to dig into a bánh mì and slices of grilled pork when I sat down to talk with him. He was raised in Japan by Vietnamese parents, and his family imports tractors from Japan and Vietnam.

Tony Fukukawa has lunch at Coffee Factory in Westminster.

(Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

Fukukawa, 22, hadn’t heard about the proposed tariffs. A stunned look crossed his face when I told him.

“Wow,” he finally said. “It’s going to damage us. It’s not good for us.”

He asked about Trump’s rationale, and I explained the president’s sentiment that Vietnam and other countries that import a lot of goods to the U.S. have taken advantage of us for too long.

“What advantage does the United States get against Vietnam?” Fukukawa wondered. “I don’t think it sounds fair at all.”

Source link